Mapping the unique experiences of women and religious persecution

What do these individuals have in common?

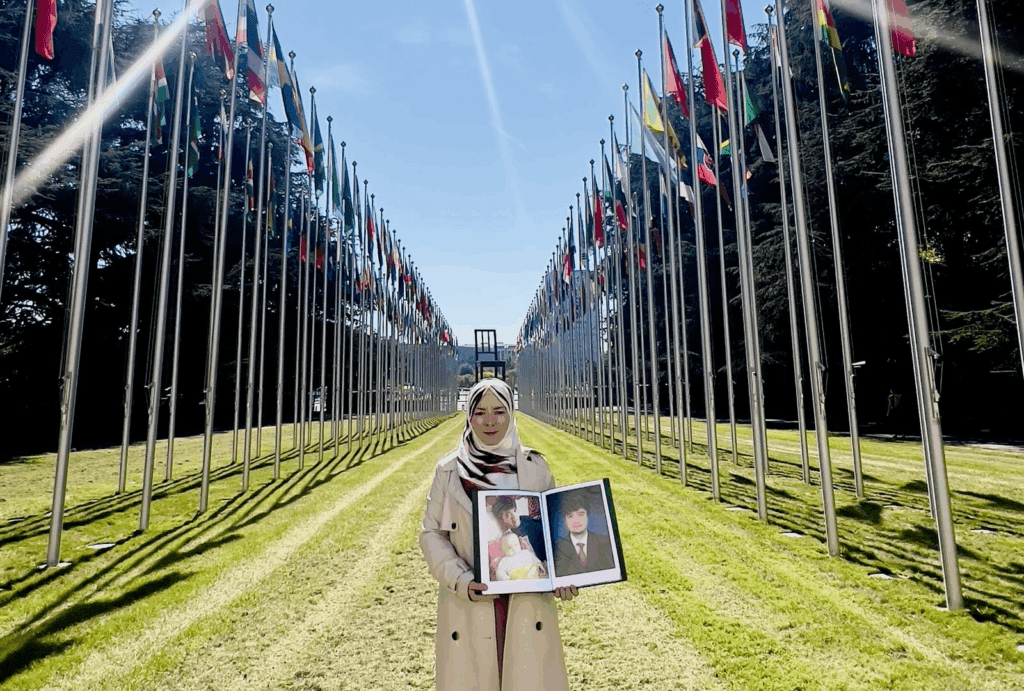

Gulmira Amin. Wife and moderator of a Uyghur news and cultural website who is imprisoned for her ethnoreligious identity and protesting against the Chinese government’s treatment of Uyghurs. She is serving a 20-year sentence in the Xinjiang Women’s Prison.

Mahsa Amini. A 22-year-old Kurdish Iranian woman whose death in police custody sparked a national movement. She had been accused of violating Iran’s mandatory hijab dress code.

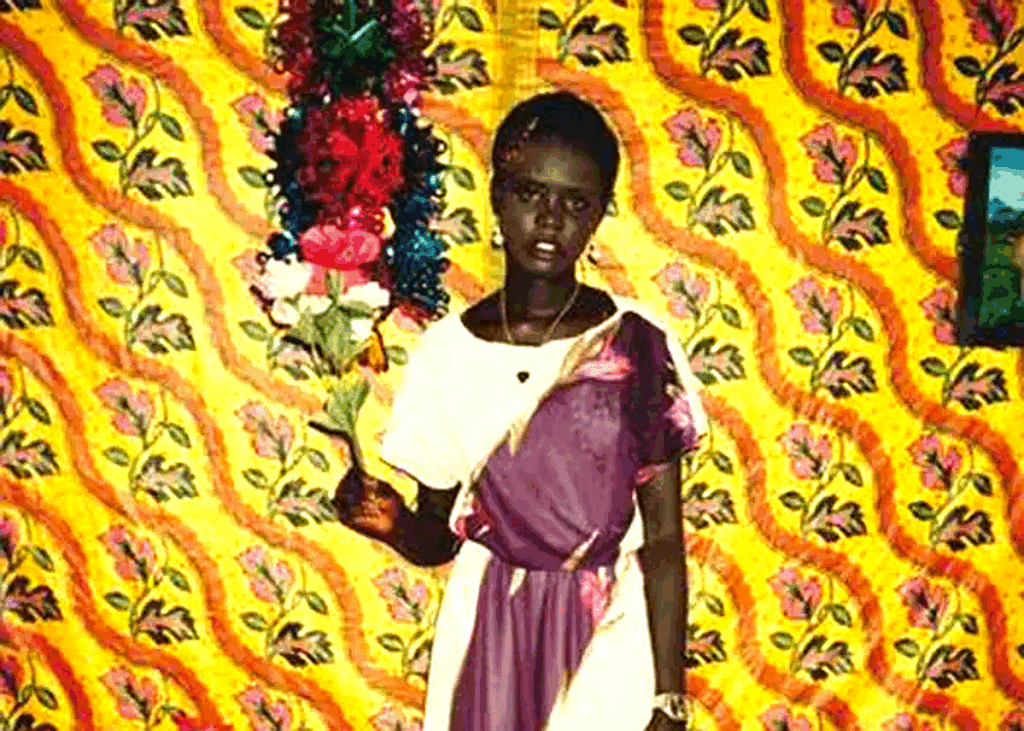

Mariam Ibrahim. A Sudanese Christian mother who was arrested for apostasy, imprisoned with her nine-month-old son, and sentenced to death. She gave birth to her second child in prison before an international outcry resulted in her release.

Rhoda Jatu. A Nigerian woman who was jailed for a perceived blasphemous message she sent via WhatsApp in response to the religiously motivated murder of Deborah Yakubu. She was granted bail after being detained for more than six months and was relocated to a safe, undisclosed location.

Saba Masih. A Catholic girl from Pakistan who was kidnapped at 15 and forced to marry and convert to Islam. Pakistani police are reportedly refusing to help.

Akhtar Sabet. A daughter and an Iranian nursing student who was expelled from university without receiving the associate degree in nursing she had earned. She was later hanged because of her Baha’i faith.

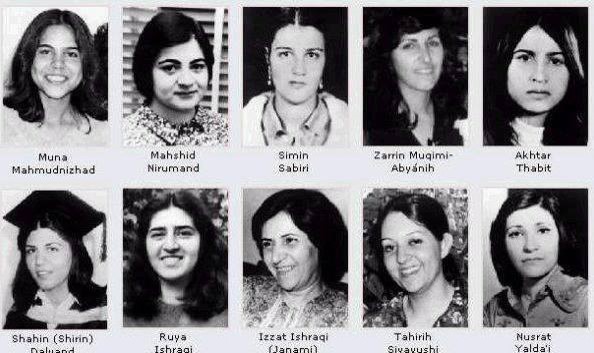

Let’s look in more detail at Akhtar Sabet’s story. On June 18, 1983, the Iranian government executed Akhtar along with nine other Baha’i women. Their names were Mona Mahmoudnejad, Roya Eshraghi, Simin Saberi, Shahin (Shirin) Dalvand, Mahshid Niroumand, Zarrin Moghimi-Abyaneh, Tahereh Arjomandi Siyavashi, Nosrat Ghufrani Yaldaie, and Ezzat-Janami Eshraghi. The women’s ages ranged from 17 to 57.

What was the crime they had each allegedly committed? They had refused to renounce their faith. Each woman was forced to witness the death of the woman executed before them. They were each hanged by executioners employed by the Iranian government. It must have taken incredible strength for a daughter, Roya Eshraghi, to witness the execution of her mother, Ezzat-Janami Eshraghi. Yet she, along with the others, did not recant her faith.

Last year, on the fortieth anniversary of their execution, the Baha’i international community launched the #OurStoryIsOne campaign to honor and celebrate all Iranian women, regardless of faith and background, who have contributed to freedom of conscience and gender equality over the years.

Like Akhtar Sabet and the other nine Baha’i women, the women and girls whose names are mentioned above have all had their freedom of religion or belief cruelly violated. They represent tens of thousands of others, both named and unnamed, in countries worldwide who have experienced profound human rights violations because of their religious beliefs or nonbelief. These violations—many of them gender-focused—have included discrimination; forced marriages and religious conversions; rape; sterilization; the denial of access to education, health care, and work; and imprisonment, torture, and even death.

Some well-known advocacy organizations have recently sought to better understand the interaction between gender and persecution based on freedom of religion or belief. These groups include the United States Commission on International Religious Freedom (USCIRF) and several United Nations special rapporteurs on freedom of religion or belief, along with the All-Party Parliamentary Group for International Freedom of Religion or Belief; Open Doors International; Aid to the Church in Need; Stefanus Alliance; and FoRB Women’s Alliance—the group with which we are affiliated. (FoRB stands for “freedom of religion or belief,” which is what religious freedom is commonly called within the international community.)

The collective findings are clear: Women and girls experience compound persecution because of both their religion and gender, as well as political and economic stressors, and cultural norms that masquerade as religious dicta. Governments often commit and/or tolerate these violations. Authoritarian regimes often feel threatened by women and girls who, despite their marginalization, are key to the strength and continuation of families, communities, and cultures. As a politically less powerful group, women and girls also make easy targets when a regime believes its power or authority is on the line.

Persecution also takes place behind closed doors, in households and within communities. Family or community members are frequently the perpetrators, and their abuses are especially difficult to uncover. They often go unreported or underreported. The perpetrators in these cases are often less likely to be held accountable than those who commit violations against men.

In 2023 the FoRB Women’s Alliance conducted a global multifaith study of women and freedom of religious or belief, in partnership with the London-based advocacy group Gender and Religious Freedom.

Our study set out to explore the advocacy work currently being undertaken in this space—largely by women and girls, many of whom are active at the grassroots level. Our goal was to create a preliminary mapping of advocates and practitioners. We also aimed to chart the challenges of working in this area, and opportunities for empowering and accelerating this work.

Without this type of research, which documents the current landscape, those who are trying to make practical differences in communities worldwide will continue to face the same obstacles again and again.

Our research revealed roadblocks that women and FoRB advocates repeatedly encounter, but it also uncovered some hopeful avenues for future action. These roadblocks—and the innovations needed to overcome them—speak to the systemic nature of the existing challenges. These challenges are faced not by one or another religious group, here and there, or by a particularly disadvantaged group of women. They are global challenges, impacting women and girls and their communities worldwide.

Here are five key findings from these conversations with women and men around the world about how we can best advance freedom of religion or belief for women.

Key Finding 1: FoRB advocacy often takes place in a “silo,” unconnected with advocacy for other human rights, such as women’s rights.

Across cultures and geographies, women and girls with minority beliefs face significant discrimination and persecution by means that are linked to their gender. In many places women additionally receive little or no education about their legal rights, and too often they suffer from the effects of violent, complex, and hidden attacks because of their chosen faith or belief. Participants in this FoRB research study underscored all these facts. Yet being a female does not lessen a person’s human right to freedom of religion or belief.

The forms of FoRB-related persecution that women and girls face are further buried by the way various advocacy groups often operate within “silos.” There is often little collaboration between those who would speak on behalf of women in the courts, the political realm, and even within their religious community. In addition, the false division between freedom of religion or belief and women’s rights also impedes advocacy efforts.

Key Finding 2: The exclusion of women from power structures also undermines efforts to address FoRB violations committed against women and girls.

Historically, efforts to address FoRB violations have excluded women and their gender-specific concerns. While numerous nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), think tanks, and humanitarian groups focus on defending and advancing FoRB generally, male leadership of the FoRB movement, including in the West, has often dominated the space. Many NGOs and leaders of the FoRB movement fail to comprehensively integrate women at every level. Women have not been equal participants in decision-making, nor have they had equal access to information about FoRB violations. The result is that those women who advocate for their FoRB rights have often found their efforts thwarted, undermined, underresourced, or unacknowledged.

Key Finding 3: Cultural norms masquerading as religious dicta can be creatively and courageously challenged.

There are passionate, committed, and gifted people working to build positive change alongside those women and girls most affected by FoRB violations by addressing belief systems and mindsets based upon patriarchal and religious norms. There are good examples available of grassroots projects and training curricula that can be shared with others in this field. Participants in our study called for more support for these creative and courageous programs—especially at the grassroots level. These efforts require a deep commitment from all who are willing to engage, as creating lasting change is challenging and requires a huge investment of resources and time.

Key Finding 4: Collaboration is a form of empowerment and can increase capacity, influence, and relief.

When communities facing FoRB violations can connect across locations, regions, and nations to collaborate, the results can be significant. From the participants in this study, there was a clear request to have a shared platform or collective. This would allow collaboration and partnership, access to training, support in advocacy, shared innovations, and access to entry-point resources. This desire to work in collaboration was evident in the examples study participants gave of their current practices and future strategies.

Key Finding 5: An external catalyst is needed to make the structural changes necessary to accelerate advocacy in this space. Women, who are so often disempowered, do not have the necessary resources to “create a space for themselves at the table.”

To accelerate FoRB across the globe, the vitality and capacity of women and their advocates must be brought to the “banquet.” They must be able to speak and act for themselves and their communities; they must be represented, understood, resourced, and activated. This can happen only when women have access to resources that will allow their skills and ideas to flourish. They must be given access to places of power and be involved in decision-making about policies, laws, budgets, and processes.

The Road Ahead

This groundbreaking report encapsulates the experiences of research participants who are working to advance religious freedom or belief for women. Based on this, we have also developed specific recommendations—for both civil society groups and governments—that address each of the challenges above. These are concrete recommendations focused on training and education, funding, sharing data and resources, and amplifying the voices of women in all aspects of advocacy work. The full report, including recommendations, can be found at forbwomen.org.

Since women account for more than half of the world’s population, it is incumbent on activists, NGOs, and governments to incorporate gender perspectives when addressing religious freedom violations. Now, for the first time, we have a vivid picture of the landscape we face, both its challenges and successes. And most important, we have a road map forward.

Lou Ann Sabatier and Judith Golub are cofounders, along with Farahnaz Ispahani, of FoRB Women’s Alliance. FoRB Women’s Alliance is a global community of religious freedom and human rights advocates and future leaders with a shared vision: advancing freedom of religion or belief for women. As a global human rights accelerator, we work across countries, regions, and sectors to increase the impact of stakeholders working on issues focused on the intersection of FoRB and women’s rights.

This article is reprinted from Libertymagazine.org