In September 2022, Muhammad Naeem Chatta Qadri urged a raucous crowd gathered in a small town in Punjab, Pakistan to kill all pregnant Ahmadi Muslim women and make sure that no new Ahmadis are born. Qadri, who belongs to the far-right extremist political party Tehreek-e-Labaik, also had proclaimed that any newborn Ahmadi “insolents” would not be spared. Qadri’s vitriol, which is tantamount to incitement to genocide under international law, was the first verbal assault directly targeting Ahmadi Muslim women in Pakistan. What was not new was his dehumanizing of Ahmadi Muslims who have lived under perpetual threat since the country’s creation in 1947.

Mirza Ghulam Ahmad founded the Ahmadiyya Muslim community in 1889 as an Islamic revivalist movement that sought to bring back Islam to its original teachings of peace, love and justice. While Ahmadi Muslims constitute only 0.22% of Pakistan’s population, their belief that the founder of their community is a subordinate prophet to the Prophet Muhammad is anathema to mainstream Muslims. Religious hardliners deem Ahmadiyya beliefs to be blasphemous and under Pakistan’s notorious blasphemy laws, they could face death. A PEW Research study published in September 2023 found that a staggering 75% of Pakistani Muslims believe these laws are necessary to protect Islam in their country.

Pakistan’s relatively short existence often has been marred by controversy, not least because of the power of its far-right clergy and the many instances of vigilantism to which the government has reacted to with impunity. The government, pandering to extremists early in its constitutional history, turned Jinnah’s vision of a multireligious, multicultural nation-state into effectively a theocratic republic: the 1974 amendment to the constitution rendered a formal definition of a Muslim, excommunicating Ahmadis from the fold of Islam. In 1984, Ordinance XX was passed which made it illegal for Ahmadis to “directly or indirectly” pose as Muslims, including the use of the Islamic salutation, ‘peace be upon you,’ and referring to Ahmadi places of worship as mosques.

In April 2020, 55-year-old Ramzan Bibi became the first Ahmadi Muslim woman arrested under the blasphemy laws. Her monetary donation to a local non-Ahmadi mosque had been refused because it came from a member of the Ahmadiyya faith. When Ramzan Bibi inquired why her donation had been refused, she was verbally and physically assaulted, sustaining significant physical injuries. The altercation drew a wider crowd, and radical clerics involved the district police and falsely alleged she had committed blasphemy against the Holy Prophet. She was arrested and charged without due process and currently awaits trial in a local prison.

The fate of Ramzan Bibi underscores that Qadri’s vile rhetoric is not merely a polemical exercise but that his incitements can spur violence that is met with impunity. Pakistan regularly has drawn international condemnation for its treatment of religious minorities and has not fulfilled its obligations under international law. While Pakistan ratified the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights in June 2010, it made sweeping reservations to several key articles, including Articles 18 and 19 that guarantee the freedom of religion and expression respectively. Amnesty International has called on Pakistan to withdraw what it calls these “obstructive and legally impermissible” reservations that threaten the integrity of the UN human rights treaty system.

Under Pakistan’s draconian anti-Ahmadi laws, Ahmadis have been kidnapped, murdered and imprisoned arbitrarily, their homes and properties destroyed, their mosques come under siege and even their graves desecrated. However, the deadliest attack on the community occurred in May 2010, when gunmen opened fire on two Ahmadi mosques in Lahore, killing more than 80 worshippers. The Lahore attacks were a watershed moment for Ahmadi Muslim women in Pakistan, for the renewed security concerns meant even the simple enjoyments of their faith, such as attending Friday and Eid prayers, no longer were possible.

Notwithstanding the unique plight Ahmadi Muslim women face in Pakistan, their stories largely have not been told in mainstream media. A recent study by the Centre for Law and Justice (the CLJ study), explored the predicament of religious minority women in Pakistan. The study found that Ahmadi women’s experiences of harassment, discrimination and violence were more severe than were that of other minority groups, including instances of violence, being compelled to hide their identity out of fear of being denied jobs or being bullied in educational institutions; and being asked to avoid confrontations in schools, universities and workplaces in order to not be accused under the country’s blasphemy laws.

Another study undertaken by the Institute of Development Studies (the IDS study) focuses specifically on the predicament of Ahmadi Muslim women from marginalised socio-economic backgrounds in Pakistan. It echoes the findings of the CLJ study and underscores that Ahmadi women who live in poverty experience ‘double jeopardy:’ their experiences of violence, discrimination and harassment are exacerbated due to their socio-economic condition, with the injustices they face not being reported by the media. The IDS study found that respondents’ main concern was the curtailments to their liberty due to Ordinance XX and its trickle-down effect that includes being denied access to Ahmadi mosques, forbidden to partake in peaceful religious activities and unable to mark important occasions.

Both studies speak of an entrenched and worsening system of state-sponsored persecution of Ahmadi Muslim women in a climate of impunity. Across national institutions (both governmental and educational) and workplaces, special measures compel Ahmadi Muslim women to reveal their identity, particularly when acquiring national identification documents: these documents require a signed declaration that the community’s founder is an ‘imposter’. Moreover, due to their recognisable manner of observing the hijab, Ahmadi Muslim women often face difficulties using public transport that frequently display anti-Ahmadi posters. They are also refused service when shopping, with many stores displaying signs denying them entry altogether, and they frequently are denied healthcare, particularly if they are from deprived socio-economic backgrounds.

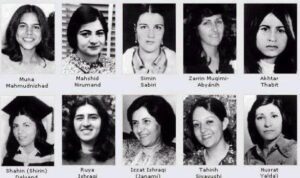

Despite the heinous persecution they face, Ahmadi Muslim women have shaped the trajectories of their personal journeys through a spirit of common humanity rather than permitting hate to dictate their existence. Such a spirit springs from the creation of a women’s organization 100 years before Qadri launched his virulent attack on expectant Ahmadi Muslim mothers. The Ahmadiyya Muslim Women’s Association was established in 1922 for the social, educational and spiritual advancement of Ahmadi Muslim women and was ground-breaking as one of the earliest associations for women to exist at the time. (The All India Women’s Conference considered to be the oldest was formed five years later in 1927.) My great grandmother led the Association for its first 36 years. During this period, while women fought for suffrage on the global stage and racial segregation divided America, the Ahmadiyya Muslim Women’s Association had established departments with dedicated functions, including finance, education, moral training, health and fitness, industry and handicraft and social welfare.

When my great grandmother was nominated to lead the Association in 1922, only 13 women surrounded her. Today, an estimated 70,000 members of the Ahmadiyya Muslim Women’s Association in Pakistan continue to serve their local communities in a range of capacities – from fundraising for the construction of wells in the water-scarce regions of southern Pakistan, empowering rural women through different sewing and handicraft schemes, teaching in community-run special educational need schools and serving in community-run hospitals as doctors and nurses. Even as Qadri and his proteges called on the murder of pregnant Ahmadi women, Ahmadi Muslim women provided specialized gynecology services at Zubaida Bani Wing in Rabwah to thousands of local women, notwithstanding their religious affiliations, and often completely free of charge.

Having grown up in Pakistan as an Ahmadi Muslim woman, I have personal experience of the formidable challenges that face women from my community in a country where our very existence is criminalized. The 1974 riots forced my grandmother to flee her home in Lahore and sectarian violence widowed my 32-year-old aunt in 1999. My mother, who served as a primary school teacher for 25 years in prominent private schools in the country, was never permitted to teach a component on Islam. In November 2015, an angry mob burned down a chipboard factory owned by my uncle and six residences in the area. Rioters entered his home while he and my aunt were trapped inside, before they managed to escape unnoticed. Their home was burned to the ground.

While behind every atrocity, there are stories of personal struggle and loss, it is the stories of resilient forbearance and not responding to hatred in kind that have inspired generations of Ahmadi Muslim women in Pakistan. We draw strength from our belief that struggle is good for the soul if prayer is its firm companion, and we are encouraged to emulate the Prophet’s example in praying even for one’s foes. In doing so, we continue to rewrite our stories of struggle to ones of serenity of faith and grit.

Ayesha Malik is the Regional Correspondent for the Oxford Human Rights Hub Blog and the Editor of the Law and Human Rights Section of the Review of Religions Magazine. She received her LLM from Harvard Law School in 2009.