What is it about the murder of 22-year-old Mahsa Amini that continues to spark unprecedented rage? The truth is that this rage has existed for the 43 years of the Islamic Republic’s reign in Iran, but Mahsa’s murder was the kindling that ignited the largest mass demonstrations, led by women, that have taken place in years. These protests exploded because Iranian women and men know that the current regime offers them no chance for freedom or dignity. To take matters into their own hands in search of their basic rights, Iranian people are risking it all as they take to the streets chanting three simple words: “Woman, Life, Freedom.”

For more than four decades, the Iranian regime has privileged its interpretation of Islam as the law of the land, levying heavy penalties for those who violate its rules while arbitrarily displaying its power with the ebb and flow of the so-called “moderates” and “hardliners.” Laws are strictly enforced by some and relaxed by the others, with justice and the rule of law often absent in the courts. Women and religious minorities are categorized legally as “second-class citizens” according to the Sharia-inspired penal code, with their chances of justice cut in half.

As government officials enforce corrupt political and economic policies that impoverish the masses, they seek to distract society by controlling women’s personal spaces through mandating the wearing in public of the hijab. Hijab enforcement thus has become a visible symbol of the government’s state power over the public: when they tighten the spigot the pressure builds and acts of civil disobedience surface. When it is loosened, the pressure is somewhat released and people experience a temporary and artificial sense of freedom, a sentiment which offers the leaders some political capital.

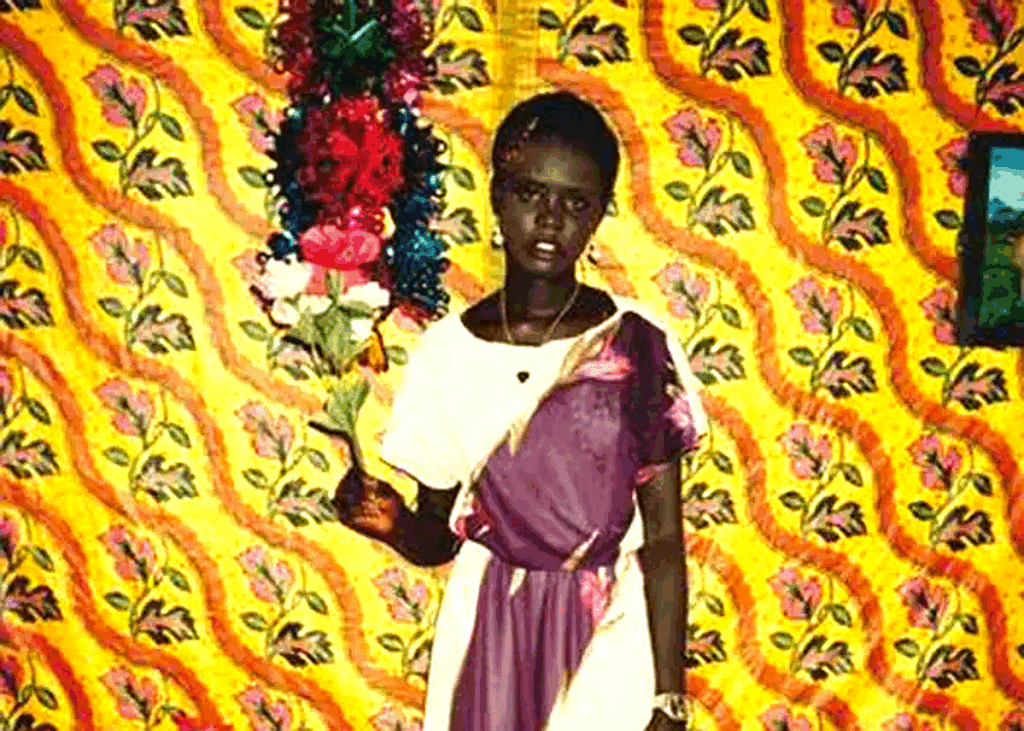

Wearing the hijab was not always part of Iran’s culture and traditions. Ancient Iranian paintings and poetry depict the details of a woman’s hair and praise her beauty and grace. It was only after the rise of Islam that hijab became part of the dress code. Even then, the practice was not uniform. In 1935, Reza Shah Pahlavi, inspired by the notion of French laicite, mandated the removal of religious garb including veils, niqabs and headscarves in public educational institutions. In hindsight, the transformation this change inspired was too rapid for some traditional sectors of society. But these mandates eventually were eased and during the reign of Reza Shah’s son and successor, Mohammad Reza Shah Pahlavi, miniskirt-cladded women walked alongside women in veils in public places.

But since the 1979 Islamic Revolution, the hijab has morphed from its original religious purpose and instead has become an instrument of government control and manipulation. To establish his credibility after being elected in 2021 with the lowest level of participation in the Islamic Republic’s history, President Ebrahim Raisi sought to enhance his power by subjecting half of the population, the women, to compulsory veiling with stricter hijab laws and heavy penalties for violators. He sought to commemorate July 12 as a National Day of Hijab and Chastity, a day inspired by the struggles of Iranian clergy over 90+ years ago who fought against Reza Shah’s push for modernization and rejection of the veil. Raisi justified compulsory veiling as “preventing evil” and referred to those who defy the wearing of the hijab as “corrupt,” or “fa-sed,” which literally means contaminated in Persian.

Such government control and arbitrary manipulation of the law and religion have created for much of Iranian society a sense of unpredictability, insecurity and powerlessness. The murder of Mahsa Amini struck many Iranians to their core because it reminded them of their own vulnerability and that any of their personal choices—of attire, expression and entertainment— could lead them to the same fate as Mahsa.

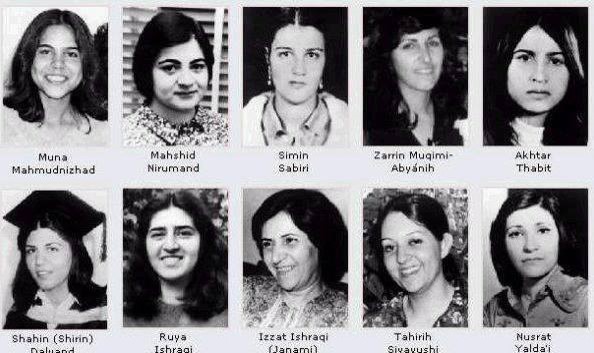

Living in the Islamic Republic of Iran is already a struggle, regardless of one’s religious affiliation, but it’s particularly perilous for the country’s religious minorities. As second-class and third-class citizens, depending on their level of recognition in the Islamic Republic’s constitution, Iran’s religious minorities endure marginalization and restrictions because of their faith or beliefs. This is a sad reality for many indigenous religious groups, such as Zoroastrians, Bahais, Dervishes, and others such as Jews who have been in Iran for millennia.

One of these restrictions in post-revolution Iran is the obligation of minority women to follow the Islamic hijab, even if this practice does not represent their own religious beliefs. This strict enforcement of a uniform dress code is hard for anyone who desires self-differentiation and most challenging for the adherents of non-Islamic religions and those who are secular. Ironically, these groups are most likely to obey these laws and follow the Islamic dress code because they are afraid of the enhanced risks and consequences of their defiance, not just for themselves but for their community. Second-class citizens by definition often feel compelled to comply with the majority to not jeopardize the limited rights that they have.

Ultimately, women and religious minorities share a common fate in Iran. Like religious minorities, women are regarded as half a person before the Sharia court of law. Their testimony is worth half of the value and their life half of a man’s. This categorization as less valuable and “half human” lays the societal grounds to regard women as “less human” and justifies and facilitates the practice of violence against women.

But increasingly, even many adherents of Shia Islam do not support the concept of the hijab as a mandate on non-willing citizens, and they vehemently oppose the exercise of violent punishment, including lashes, beatings and humiliation as a method of enforcement. They view these actions as un-Islamic and bad for religion. This sentiment was reflected in a 2020 public opinion survey on religion in Iran, conducted by GAMAAN, a research institute based in the Netherlands. The survey found that at least 50% of the population are turning away from Islam or religion altogether– most likely as a result of negative experiences with religion in their homeland. The same study also found that 70% of the people reject the idea of mandatory hijab, including nearly 40% of the population that believes in hijab as a personal choice.

Beyond the statistics, this sentiment is evident in the videos emerging from Iran, where hijabi women and girls demonstrate with non-hijab wearing women in their mutual fight for freedom. This fight is about rejecting the control of the Iranian government over women’s personal space and reclaiming their dignity and autonomy. Ultimately, with every uncovered braid and cut hair, it is about an alternate vision of Iranian identity.

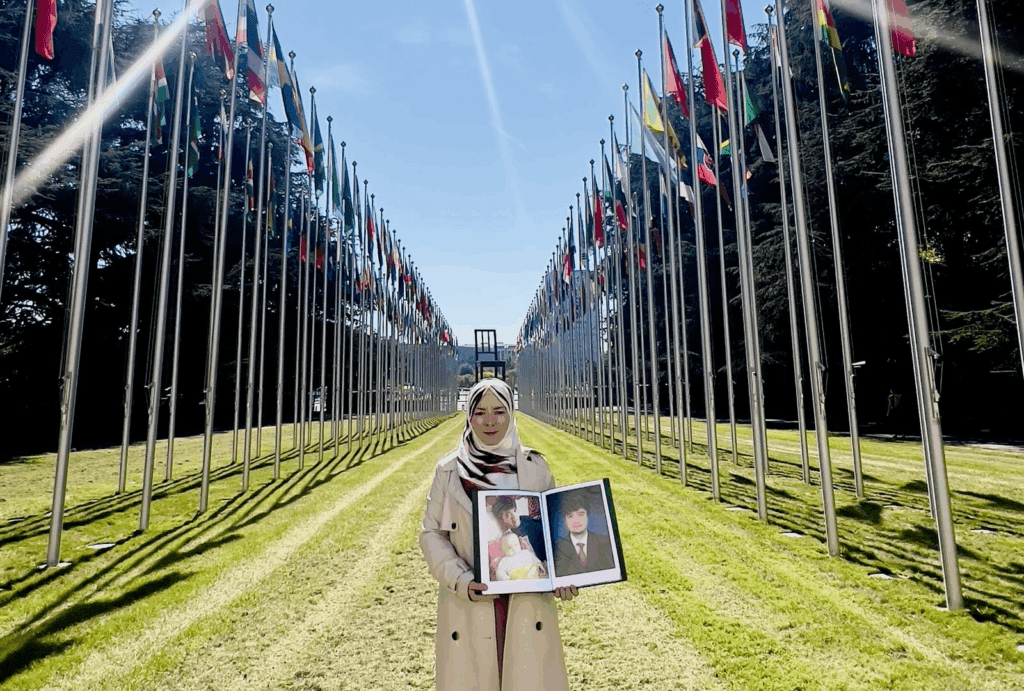

Marjan Keypour Greenblatt: Born and raised in Iran, Marjan is a human rights activist and the founder of ARAM and StopFemicideIran. She is a non-resident scholar at the Middle East Institute and a member of ADL’s Task Force for Middle East Minorities. Follow her on Twitter @MarjanKG