A lot can happen in eight years. Children learn to walk and talk, tie shoes, and read. Young people come of age, fall in love, get married. Old people turn gray, grow a little wiser, move a little slower. Eight years is enough time to master a skill, build a career, fulfill a dream.

On the other hand, eight years is a long time to wait — for answers, for relief, for justice. The people of the Nineveh Plain will tell you not enough has happened in eight years to restore the dignity, security, and sense of community shattered by ISIS militants who laid siege to their ancestral home in the pre-dawn hours of August 3, 2014.

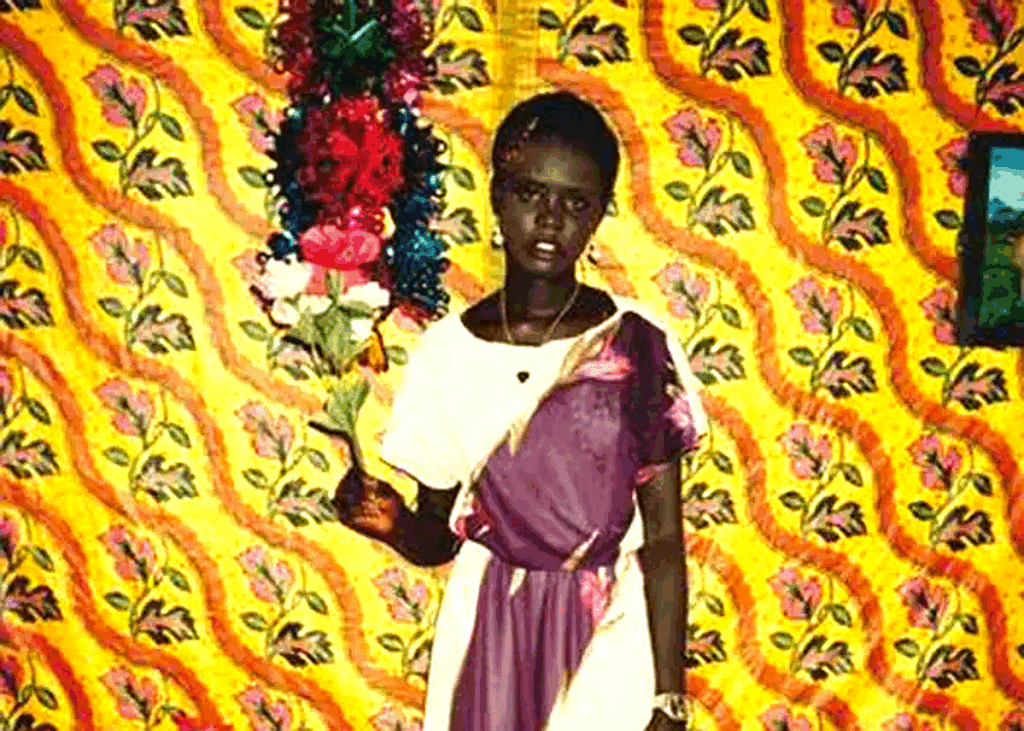

In the first week following the attack on Iraq’s Sinjar region, ISIS kidnapped or killed an estimated 12,000 people, mostly indigenous Yazidi, but other religious minorities as well. They summarily executed Yazidi men and older women. Younger women and children were trafficked as sex slaves. And young boys were recruited and indoctrinated as ISIS soldiers.

In that murderous summer, a stunned international community rallied to help the Yazidis. Who can forget the dramatic images of hundreds of thousands of desperate innocents fleeing to the top of Mount Sinjar? Or the multiple airdrops of food and water to aid refugees trapped atop the mountain in sweltering heat. The media chronicled the exodus of some 400,000 Yazidis who sought shelter and protection in IDP camps. By 2016, the United Nations, United States and other nations had recognized the atrocities perpetrated by ISIS as genocide.

But in the eight years since ISIS unleashed destruction, the plight of the Yazidis has largely faded from view. New atrocities have replaced the old headlines: the fall of Afghanistan, Russia’s unprovoked invasion of Ukraine, millions dead from the global pandemic. Even so, the Yazidi community remains desperate. Today, more than 220,000 Yazidis languish in IDP facilities, unable or unwilling to return home. They live in squalid conditions. Access to the basic necessities — adequate food, water, electricity — is limited. Employment opportunities are scarce. Even basic healthcare is lacking. More than 2,700 Yazidi, mostly women and children, are still missing. And no organized international effort exists to find them.

“I think it’s a stain on all of our countries that espouse a commitment towards defending religious freedom and protecting religious minorities that we haven’t done the hard work of actually trying to effectuate a rescue,” says Knox Thames, visiting expert at the U.S. Institute of Peace and former U.S. Department of State special advisor for religious minorities in the Near East and South and Central Asia.

Thames and others believe it is likely many of the missing women and children may be trapped in the al-Hol displacement camp in northeast Syria, a notoriously dangerous location where victims, bystanders and perpetrators of ISIS violence cohabitate.

To locate and liberate the missing women and children would be a heavy humanitarian lift says Thames, but a necessary one. “To leave them there with their victimizers is just wrong. It’s morally unacceptable.”

Also unacceptable: the wholesale impunity ISIS fighters have received, particularly after the international community designated their heinous activity a genocide. Lauren Homer is a long-time international religious freedom advocate and attorney who represents faith-based organizations. She finds the lack of any judicial consequences for ISIS members nothing short of scandalous.

“There should be trials of the people responsible,” says Homer. “They should be captured, confronted with the evidence against them, and appropriately punished. The people of northeast Syria have been calling for something like a Nuremberg-style prosecution of the ISIS fighters. It would be so important for the Yazidis and all the other people who suffered under ISIS to actually see these folks brought forward in a courtroom and be confronted with their crimes.”

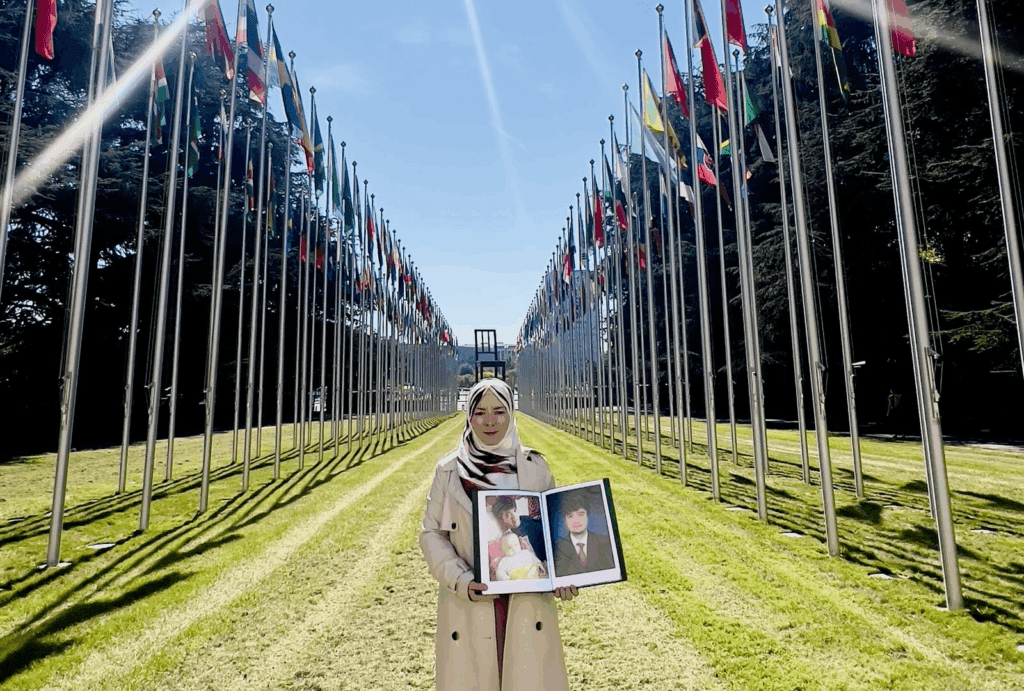

Pari Ibrahim longs for justice for her family. She lost dozens of family members in the ISIS genocide, including 19 girls who were kidnapped. Two of those girls managed to escape their captors but 17 remain lost. “What our community as a whole went through is indescribable,” she says. “You cannot explain the anger, the sadness, the hope of your family members returning. And when they return, they come back as a lifeless body, a body without a soul, without hope, without any love after the hell they went through.”

Ibrahim founded the Free Yazidi Foundation (FYF) shortly after the Sinjar invasion to provide humanitarian support to her community, particularly women who are especially vulnerable to gender-based violence and sexual assault. She says keeping the needs of Yazidi victims at the forefront of international humanitarian efforts has grown increasingly difficult: “Unfortunately, I look at my people eight years down the road, and I don’t see much difference. Funding is depleted. There is no support for Yazidis. That’s why they’re still displaced.”

Ibrahim believes more sustainable aid solutions are needed moving forward. “The problem is that a lot of the humanitarian aid is created on dependency. This is not what we want for our community. We don’t want projects that diminish after a year with no sustainable effort to ensure our people can have a better situation.”

Instead, Ibrahim points to programs like FYF’s Enterprise and Training Center, an economic incubator that empowers Yazidis to develop skills and initiatives for economic stability and independence. One such project is the Sugar is Sweet Bakery, a wholly owned and operated Yazidi enterprise, where about 100 Yazidi women receive valuable training and earn a basic wage each year.

“Some of these women were never able to read or write. Some of them never had any money in their own hands,” says Ibrahim. “Now they are the breadwinners of their families because we created something that would economically empower them.”

Much healing remains for Yazidis. Yet Ibrahim and others like her are determined to charge forward. Aid from the international community is welcome, but Ibrahim also aims to create the kinds of projects that foster self-sufficiency so that the next eight years might be brighter than the last.

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of FoRB Women’s Alliance.