While Vietnamese women play essential roles in family, society, and religious life, their contributions remain underrecognized as they face challenges in education, employment, and decision-making as well as intimate partner violence and human trafficking. Yet, there is room for faith-based communities to offer support. An understanding of the factors that shape the status of women in Vietnam is essential to help ensure the effectiveness of such support.

Social Norms and Gender Expectations in Vietnam

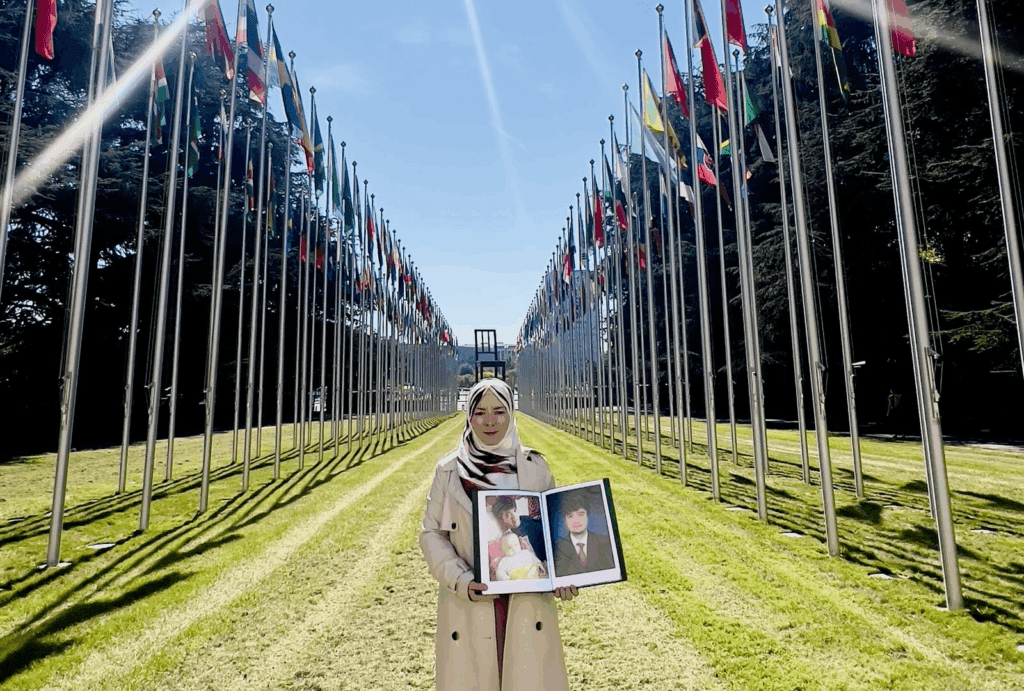

I was on a tranquil boat ride through the serene Trang An scenery complex[1], accompanied by a Vietnamese friend and a foreign visitor. The landscape—lush greenery, flowing water, and spiritual landmarks—offered a peaceful escape from urban Hanoi’s crowded streets that we had left that morning. Our boat paddler, a gracious Vietnamese woman, paddled diligently while pointing out pagodas and the surrounding mountains, narrating stories steeped in the region’s history, culture, and traditional beliefs. Despite the physically demanding work, she skillfully balanced navigating the waters while acting as our tour guide. She even managed to exchange conversations with female paddlers in other boats.

At several iconic spots, she paused to kindly offer to take group photos for us, setting down her paddles and handling our phones with care. She directed us to pose and took great pictures. I thoroughly enjoyed the peaceful surroundings and her warm presence, though I couldn’t shake a sense of guilt watching her work so hard while we relaxed.

Women paddlers in Viet Nam

Then, my foreign companion asked, “Hien, please ask her—I noticed all the paddlers are women. Where are the men?”

She smiled and replied, “Oh, the men are at home doing men’s things.”

Curious, he asked, “What kind of men’s things?”

With a hearty laugh, she said, “Something heavier… like building the boats.”

He thanked her, then muttered under his breath, “Well, paddling for hours seems pretty heavy, too.”

That moment reminded me of a common Vietnamese saying: “Đàn ông xây nhà, đàn bà xây tổ ấm”— “Men build the house, women make it a home.” I found myself questioning: if this saying were truly followed, shouldn’t a man have been paddling our boat?

Gender roles in both domestic and public life in Vietnam are deeply shaped by Confucian and Taoist influences: Confucianism being more prominent in rural areas, and Taoism in urban settings. Confucianism traditionally favors men, reinforcing rigid gender roles and placing women in a hierarchical structure where obedience and self-sacrifice are expected for the sake of family harmony. In some superstitious situations, women even are labeled as “bad luck.” By contrast, Taoism offers a more balanced view through the concept of Yin (female) and Yang (male) as complementary forces. Women are seen as, not subordinate, but bearers of soft yet powerful influence. It is not surprising that recognition of their roles and contributions is more prominent in urban than rural areas.

Vietnamese women wisely and quietly have drawn strength from Taoist perspectives, steadily proving their ability to overcome deeply rooted prejudices, superstitions, and restrictive expectations that have burdened them for centuries. Across the country, women are seen working hard, whether white-collar or blue-collar. Yet, few women make decisions for themselves and the groups to which they belong.

A Paradigm Shift: Post-Economic Reform Transformation

Following the Đổi Mới (Renovation) policy of 1986, during which Vietnam shifted from a centrally planned to a market-oriented economy, women increasingly showcased their creativity and potential, becoming active players in economic, political, and sociocultural life.

A 2018 IMF report noted Vietnam’s leadership in advancing female labor participation in Asia:

“The Doi Moi reforms aimed to build a “socialist-oriented market economy” by encouraging private businesses, ending price controls, and phasing out government enterprises, among other changes. These changes brought rapid economic growth, opened the economy to trade, and led to rapid urbanization. While a large share of the female labor force remained, and remains, engaged in agriculture, female wage workers increasingly joined the large service and foreign direct investment sectors.”[2] Vietnamese women became known for their entrepreneurial spirit. As private enterprise grew, family-run convenience stores began lining Vietnam’s main roads and alleyways, with women operating most of these stores which are similar to 7-Elevens.

While this economic transformation opened doors for women’s participation in the workforce, challenges remain. The International Labor Organization reports that Vietnamese women still bear a “double burden”,[3] —juggling full-time employment with primary responsibility for household duties and parenting children. Traditional norms casting men as breadwinners and decision makers remain stubbornly persistent, especially in rural areas.

Navigating Tradition and Modernity

In post-Đổi Mới contemporary Vietnam, the Vietnamese women’s journey against traditional gender inequality is supported by their government and international organizations. Policies, research, recommendations, and campaigns have been launched at local and central levels of administration. Yet, cultural expectations endure. Vietnamese women often walk a delicate line between subordination and autonomy—navigating expectations and pressures from family, society, and historical legacies —while continuing to care for others. For example, depending on contexts and motivation of the message, the following popular sayings are used to expect or encourage women to assume their “feminine roles”:

Giỏi việc nước, đảm việc nhà: Skilled in public service, diligent in domestic work

Giặc đến nhà đàn bà cũng đánh: When enemies invade, even women will fight

Công, dung, ngôn, hạnh: Diligence, grace, speech, and morality (four feminine standards).

It is often difficult to pinpoint exactly which and when Vietnamese women are encouraged or pressured to embody these so-called ideal traits.

In many families, multiple generations live under the same roof. Within this structure, women often assume the role of “Nội Tướng”—the “Domestic General.” They are caretakers, peacemakers, and quiet strategists, managing the needs of family members across generations, with traditional and modern lifestyles and somewhere in between, from Traditionalists (born 1925–1945) to Gen Z (born 2001–2020). In these roles, they draw upon lived experience shaped by Vietnam’s long history of patriarchal systems—legacies of feudalism, colonialism, and socialism. Navigating these layers of expectation, Vietnamese women have demonstrated remarkable resilience. Whether managing household conflicts or balancing caregiving with work, they have continued to seize opportunities to, not just survive, but flourish.

The research collection Weaving Women’s Spheres in Vietnam: The Agency of Women in Family, Religion, and Community[4] highlights how Vietnamese womanhood is full of contrasts. This compendium of research articles also emphasizes the importance of institutions beyond the family—schools, religious organizations, and community networks—as spaces where women can reconnect with their social, ethnic, and national identities.

The Power of Feminine Spirit: Religion and Belief

The majority of Vietnamese practice ancestor worship blended with Buddhism, Confucianism, and Taoism. Most religious practitioners and Buddhist temple-goers are women —without formal membership in religious institutions. These practitioners are multi-god worshippers who make up an estimated 80%-90% of the population when tallying the Mahayana or Theravada Buddhists. The second largest religious group is Catholics who make up about 7% of the population. The remainder belong to Cao Đài and Hòa Hảo, Protestantism, Islam, Baha’i, Hinduism, and other Indigenous religions. [5]

Female figures of the two largest religions in the country—Buddhist Quan Âm (Goddess of Mercy) and Catholic Mother Mary—hold significant spiritual influence. Both figures—though respectively imported through Buddhism from China and India (originally a male figure), and Catholicism from the West—have been embraced within Vietnamese culture, blending with the indigenous Mother Goddess to become sources of strength and comfort for female worshippers.

The traditional worship of Mother Goddesses (Đạo Mẫu) started in Vietnam in the 16th century and remains the most spiritual influence in Vietnam, recognized by UNESCO as an Intangible Cultural Heritage. Đạo Mẫu elevates feminine power and compassion. Through rituals and ceremonies, women seek blessings for peace, health, and prosperity, reaffirming their spiritual importance in both personal and communal life. The Mother Goddesses have developed over the past decades and, at times, its practices are seen as materialistic and superstitious. It involves folk dance, mediumship, queer performance, and shamanism. Some Vietnamese scholars argue that it is an outlet for women as they deal with gender inequality and suppression. “Devoted to female deities and influenced by Confucianism…Women are expected to play a passive, submissive and subservient role…They are not well respected and have to rely on men. The people needed a symbol, so they invented mother goddess ‘Lieu Hanh.’ She represents Vietnamese women’s burning desire for freedom, independence and happiness.”[6]

Thao Nguyen states in the journal Buddhist-Christian Studies, “While devotion to Mary motivates Catholics to live out their ethical lives in a relationship with God and other human fellows, devotion to Quan Am helps Buddhists attain ethical and spiritual values, such as compassion, patience, mercy and harmony.”[7] Most religious practitioners today might not know about the original influence of their belief or look at their religious practice from an anthropologic perspective. The fact we see is that women are central to Vietnam’s spiritual life and way of earthly life.

Opportunities for Faith-Based Engagement and Empowerment

Under Vietnam’s 2016 Law on Religion and Belief and the 2021–2030 Gender Equality Strategy, people of faith—especially women—can collaborate across faiths to serve vulnerable women in their neighborhoods and larger communities. Examples of such collaborations include:

- Multifaith Women in Charity Work: From 2007 to 2019, the southern city of Ho Chi Minh hosted a biennial series of events called Compassion Day of Religious Nuns. These gatherings brought together 432 nuns from Catholic, Buddhist, and Cao Dai communities. Collectively, they donated 7,145 gift packages valued at over 2.03 billion Vietnam Dong (about US $85,000) to people in need. Each event featured a variety of activities, including providing nutritious meals, free haircuts, musical performances, and distributing gifts to patients and staff of social welfare centers. Beyond charity work, the gatherings foster meaningful connections among nuns from different religious communities.[8]

- Local Women of Faith Clubs: Across several provinces—including Đồng Tháp,[9] Bến Tre,[10] and Khánh Hòa[11] —there are grassroots clubs for women of faith. These clubs, either single-faith or multifaith, bring together women to support one another and engage in joint charitable activities. The model was initially launched by the Vietnam Women’s Union (VWU), a government organization. These clubs often focus on serving vulnerable groups such as orphans, the elderly, and people with disabilities. The model has the potential to be expanded and replicated by faith-based groups across the country.

The Vietnam Women’s Union (VWU) is a socio-political organization affiliated with the Vietnamese government. According to its official website, the VWU is tasked with “representing the legal and legitimate rights and interests of Vietnamese women from all walks of life” and is committed to promoting women’s development and gender equality. As of 2024, the VWU reported having more than two million women of faith among its membership[12]. This initiative creates a valuable opportunity for further collaboration between the VWU and faith-based women’s groups in advancing gender equity and social welfare across Vietnam.

Vietnamese women are dynamic agents of change. They are not merely survivors of cultural expectations. They are weavers of strength, navigating tradition and modernity, subordination and autonomy, public achievement and private devotion, and secularity and spirituality. Their journey to live beyond the norms that form gender inequality continues— to one of empowerment through resilience, community, and spiritual faith.

Hien Vu is Vietnam Program Manager at the Institute for Global Engagement (IGE). She promotes religious freedom and human rights at the intersection of culture, politics, and religion. She graduated from Fresno Pacific University with a Master’s degree in Peacemaking and Conflict Studies and Hanoi University with a Bachelor’s degree in English.

[1] https://vietnam.travel/things-to-do/virtual-travel-trang-an-landscape-complex

[2] https://www.elibrary.imf.org/view/journals/022/0055/003/article-A004-en.xml

[3] https://brill.com/display/title/24128?language=en

[4] https://brill.com/display/title/24128?language=en

[5] https://www.state.gov/reports/2023-report-on-international-religious-freedom/vietnam/

[6] https://www.cnn.com/travel/article/mother-goddess-worship-hanoi/index.html

[7] https://muse.jhu.edu/article/675593

[8] http://giaithuongdaidoanket.tphcm.gov.vn/2022/10/10/cong-trinh-ngay-hoi-nu-tu-lam-cong-tac-xa-hoi-tu-thien/

[9] https://baodongthap.vn/xa-hoi/phat-huy-vai-tro-phu-nu-ton-giao-tu-cac-mo-hinh-sang-kien-cach-lam-hieu-qua-116295.aspx

[10] http://phunuxudua.bentre.vn/chi-tiet-tin?/cho-lach-to-phu-nu-ton-giao-nhip-cau-gan-ket-va-lan-toa-gia-tri-nhan-van/46559780

[11] https://baokhanhhoa.vn/xa-hoi/202409/nha-trang-phu-nu-ton-giao-tich-cuc-lamthien-nguyen-f771683/

[12] https://hoilhpn.org.vn/tin-chi-tiet/-/chi-tiet/8-chi-tieu-van-%C4%91ong-tap-hop-phu-nu-theo-ton-giao-phu-nu-dan-toc-thieu-so-%C4%91en-nam-2030-351001-6901.html