Women too often are treated as second-class citizens, especially when they assert themselves as men’s equals. In India, women are portrayed as goddesses, but the reality is vastly different. They often are treated as less than human beings, with violence against them on the increase.

According to Frontline Magazine, the National Crime Records Bureau’s (NCRB) annual report found a harrowing surge in crimes committed against women in India. With a staggering 4,45,256 cases registered in 2022 alone, equivalent to nearly 51 formally documented crimes being committed hourly, the data finds a grim increase from 2020 to 2021.

In India, women’s rights, freedom, and very survival are centered on their gender, with a family’s pride and honor resting on a woman’s reproductive capacity in a patriarchal social life and structure that is oppressive, inhumane and dehumanizing. Religion plays a crucial role as one of the most potent forces and institution: The discriminatory age-old practice of caste is a key determinant of a woman’s power and position in society.

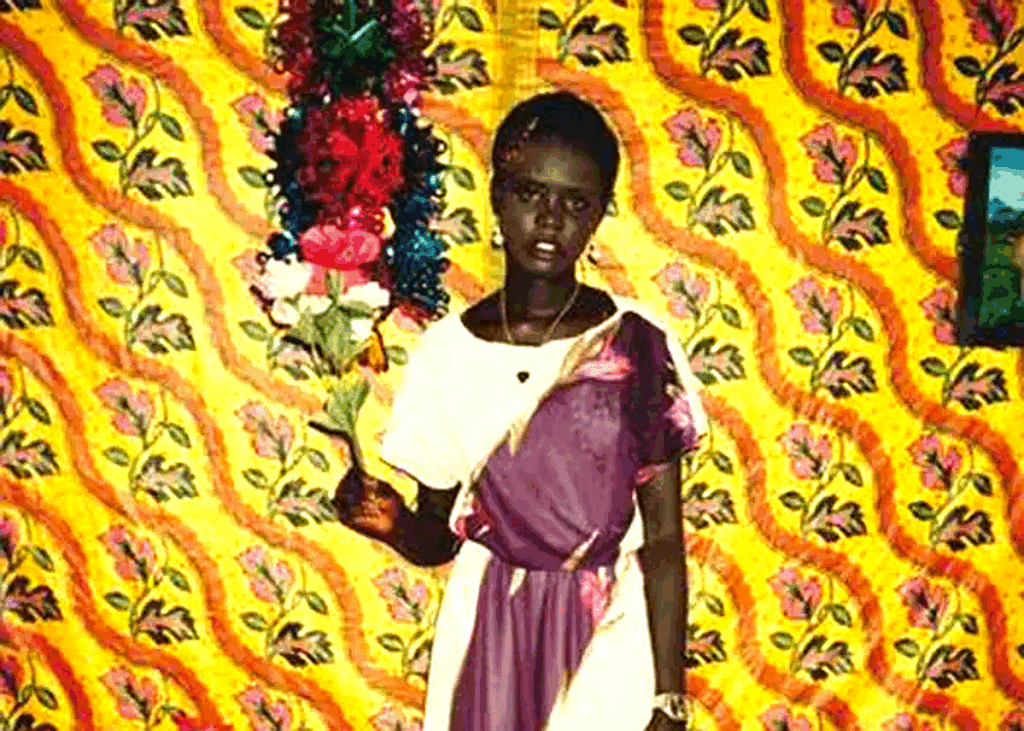

Religion has been both a boon and a curse to women’s empowerment. Indian women are celebrated as goddesses, most village deities are women, and rivers often have female names. Attaining puberty is celebrated in many Indian cultures. Yet, although India constitutionally is a secular nation that embraces diverse religious beliefs and cultures, the caste system, as experienced especially in villages across the country, curtails many people’s, especially women’s freedom, dignity, and equality.

India’s caste system

Indian society is based on the Varna system, a social stratification made up of four categories that are included in the Manusmriti, the most worshipped book for Hindus after the Vedas and which has become the basis for Indian culture, thought and practice. The Varna caste system has four categories: Brahmins (priests, teachers, and intellectuals), Kshatriyas (warriors, kings, and administrators), Vaishyas (agriculturalists, traders, and farmers), and Shudras (workers, labourers, and artisans).

A fifth category are made up of Dalits who are considered to be outside of this system. As casteless people, Indian society treats Dalits as untouchables. To be born into an untouchable caste is the worst misfortune that can befall a woman. Such a woman is a non-person, often with no right to property, no guarantee of her right to life, liberty, reputation, or the free exercise of her powers, talents, and choices. While India today is unsafe for women, that is especially the case for Dalit women. The caste system does not even consider rape and murder as crimes if they are committed against Dalit women.

Dalit Life in India

Dalits face discrimination for being, not only ‘untouchable,’ but not Hindu, Sikh or Buddhist. Christian and Muslim Dalits are even denied the very limited legal protections and employment opportunities available to Hindu, Sikh and Buddhist Dalits. Notwithstanding these limited measures, Dalits, historically the sons and daughters of the soil, largely are landless, silenced and robbed of their dignity along with the necessities of life. Many experience deprivation, discrimination and exclusion from the womb to the tomb.

Every 18 minutes, a crime is committed against a Dalit. Official police statistics issued in 2012 found that in the prior five years, every week 13 Dalits were murdered, six were kidnapped or abducted, and five Dalit houses or possessions were burned.

Dalit women face double discrimination due to their gender and caste. Every day, three Dalit women are raped, two Dalits are murdered, and 11 are beaten. Only 27 percent of Dalit women give birth in hospitals.

A 2016 publication, Policy of Dalit Empowerment in the Catholic Church in India: An Ethical Imperative to Build Inclusive Communities, highlights the conditions of Dalits in India, conditions that remain deeply concerning today.

Christian Dalits in India

Christian Dalits make up two-thirds of India’s Christians. Many Dalits converted to Christianity to escape the clutches of caste. They believed the Church would treat them as equals. But their newfound faith has not helped them achieve the equality they seek and deserve. Their discrimination is further compounded by the discrimination they face within Christianity. Dalits are under-represented in the church hierarchy, accounting for only 9 of about 200 active bishops. Furthermore, there are two separate churches, two cemeteries, and two hearse carts. Dalit women, youth, and children are especially ill-treated, and intra-Christian killings in the name of caste occur.

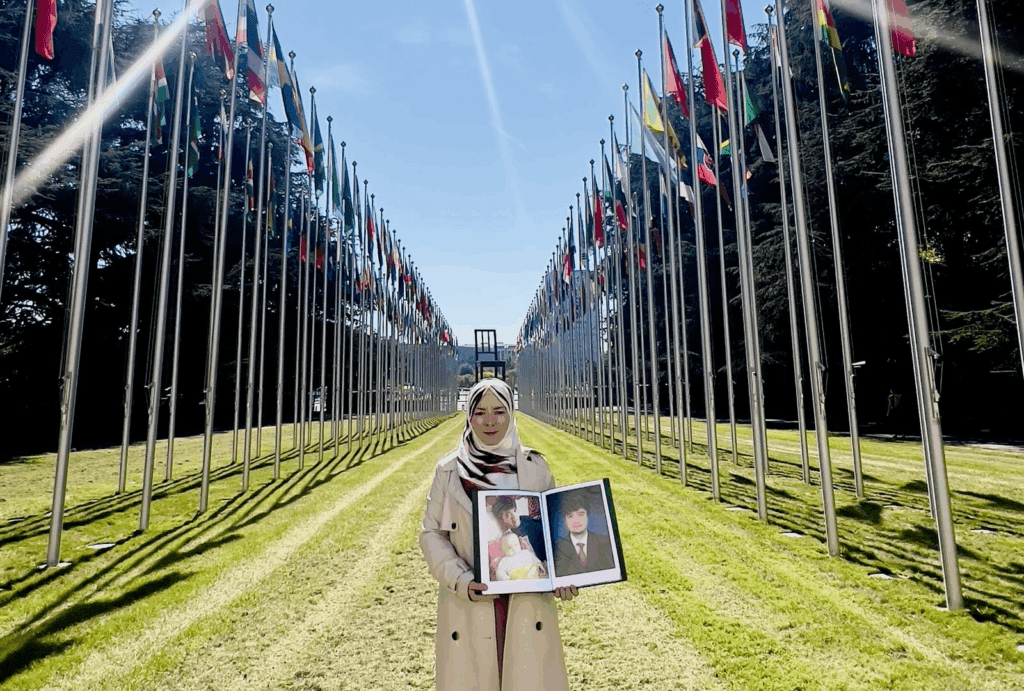

There are numerous told and untold stories of Dalit women in India, especially Dalit Christian women, who are neither part of the larger society nor the churches they belong to.

The history of Dalit Christian women is a story of oppression by the triple-headed, centuries-old monsters of caste, class, and gender.

While women generally are not included in the church’s decision-making process, Dalit Christian women fare even worse. The dominant caste men and women do not allow them to be part of the parish council which oversees the community. Dalit Christians, both men and women, are not allowed to take active roles in the prayer services and are discriminated against during church festivals. For example, in most villages, church festival processions do not take place in Dalit neighborhoods. The excuse given is that these areas are far from other Christians or that the streets are too narrow. Dalit Christians also are not allowed to pay Church taxes as such payments would allow them to demand equal rights in the festivals. The dominant caste Christians also do not allow Dalits to carry the dead bodies of their community members for burial in the main street as it is meant only for the dominant groups. They can use only narrow side streets.

Socio-Economic Status: As untouchables, Dalit Christian women face discrimination by the dominant-caste women in their villages. They have difficulty finding jobs, for which, generally, dominant-caste women are preferred. The church does not support unskilled Dalit Christian women, especially those who are elderly, from low socioeconomic backgrounds. Women and children usually live in poverty and in unhealthy areas, are malnourished and prone to get sick. They are paid less than the Dalit men and are forced to work in their ancestor’s profession. Most do menial jobs such as day laborers in agriculture, sweepers, and manual scavengers.

Sexual Exploitation: Along with being verbally and physically abused, Dalit women too often are abused sexually. The dominant caste men and youth frequently use filthy language to provoke or mock Dalit women, leading to disputes among the different caste groups. The Prevention of Atrocities Act of 1989, which includes provisions that are supposed to safeguard Dalit women against sexual assault, does not even apply to Dalit Christian women because they lack Scheduled Caste status. Only the activism of Dalit community members ended evil practices such as the following:

- Siruthondamathevi is a missionary parish of Alagappasamuthiram in the Archdiocese of Pondicherry-Cuddalore in Tamil Nadu, in the southern state of India. The dominant Hindu caste takes advantage of the minority Dalit Catholics living there. Because they lack protection, Dalit Christian parents used to send their young girls to work outside until they got married. Male Hindu caste members would visit Dalit houses in the evenings, send the men away, and then rape their wives. In one case, when members of the Dalit Christian community protested with the help of Viduthalai Churuthaikal Katchi(VCK), the local political party, their houses were destroyed and they were attacked. Fortunately, this evil practice no longer takes place because of political intervention that resulted from advocacy efforts.

- Women customarily had to spend their nuptial night with the dominant caste’s village leader. If Dalit women refused, the dominant caste denied them food. The situation of these women is explored in the documentary Echam Micham. The intervention of many social activists largely ended this evil custom.

The Unseeable Women

While Dalits and Dalit Christians are treated as untouchables, there is a Dalit sub-caste called the Thurumbar (or dobies in Tamil) who are forced to wash the Dalit’s clothes. It is believed that even the shadow of the Thurumbar would make a person impure. They live outside villages, mostly in huts on land they cannot own, and work washing dead bodies and the menstrual cloths of the girls who attain puberty, and bearing torches during the procession of the deities. In return for this work, they are allowed to beg for food at night.

Conclusion

Pope Francis emphasized the importance of recognizing woman’s contributions while calling for unity and education to promote women’s rights and dignity. Women, including Dalit woman, should not be discriminated against based on religion, gender, or caste. Religion must never be used as a tool to curtail women’s freedom or to empower themselves.

Women need to organize and fight against all forms of caste discrimination and social disparities in society and in the Church. I have dedicated my life to this fight. For example, when I was working in the Tamil Nadu Bishops Council, Commission for Scheduled Castes and Backward Classes, I started and coordinated for years a forum, Dalit Christian Women for Social Change. The forum trained Dalit Christian women on leadership skills and their socioeconomic and political empowerment, and worked with women villagers. Due to this training, some women were able to counter domestic violence, become entrepreneurs, and better understood the caste discrimination they face and ways to respond.

The growth of Indian society and Christianity depends on the equal treatment of women at all levels, including equal opportunities in education, employment, and politics. Much work remains to be done.

Dr. Robancy A. Helen is from Tamil Nadu, South India and is a member of Messengers of the Mary of Magnificat. With an academic background in English, social work and theology, she has written about and has actively addressed Dalit and women’s issues. Recently, she served for five years as the program coordinator in the Catholic Bishops’ Conference of India’s Office for Scheduled Castes/Backward Classes. She holds a doctoral degree in English Literature and trains Catholic children and women in leadership and social issues.