Despite great advances in gender inclusion over the past fifty years, women are still woefully underrepresented in decision-making across the world. Even worse, Georgetown University’s Women, Peace and Security Index[1] finds that the implementation of gender equality laws has slowed in recent years as the world grapples with ‘compounding and multilayered crises that undermine the status of women and threaten to roll back decades of progress’. Women are not naturally included in policy discussions to advance peace – or freedom of thought, conscience and religion – for that matter. If that were the case, women would be equally present at the table given that they constitute over 50% of the world’s population.

Not all women are peacemakers, even though the roles they have played in building and sustaining relationships within families and communities for thousands of years has certainly honed these skills. But the “feminine” characteristics that are found in both men and women that privilege caring, compassion, mediation and dialogue, over more “masculine” traits of strength, dominance, assertiveness and competition, need to play a more prominent role in our lives if we are to flourish – and the easiest way to make that happen is to nurture more women to become public leaders. We also need to encourage male champions to support women in this role. These feminine characteristics are the basis for alternative models of leadership that normally are not predominant in our world and, quite frankly, are sorely needed.

Such characteristics are also desperately needed within religious frameworks, which generally are based on patriarchal traditions sourced in ancient cultures where women’s roles are marginalized and often excluded from the public domain. In these frameworks, where men hold positions of authority and are privileged over women, it is even harder for women to take up leadership roles and advocate for their own freedom of thought, conscience and religion, let alone that of others, something so needed if we are to advance peace.

In my role over the past eight years as director of religious engagement for Search for Common Ground (Search), the world’s largest NGO dedicated to peacebuilding, I have had the privilege of working with religious actors, both women and men, to expand the voice of women and advocate for religious freedom while at the same time maintaining respect for deeply held religious values. We have found that through sensitive handling, profound listening, and deep discussion using a religious lens, it is possible to find a path that intersects gender rights and freedom of religion and belief (FoRB)[2] that enables both to flourish simultaneously.

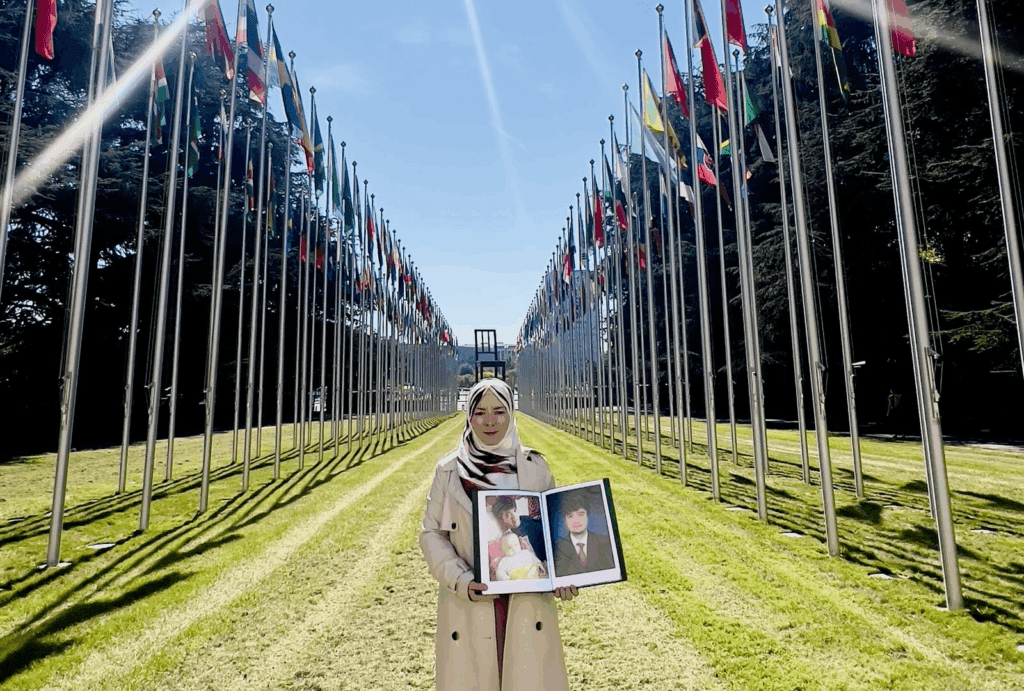

The Joint Initiative for Strategic Religious Action (JISRA), a consortium run five-year project, lobbies and advocates for FoRB across seven countries. JISRA places particular emphasis on including women in decision-making and on gender equality. We work to expand the space for positive gender roles, for both women and men, within religious communities and lobby for this expansion while promoting FoRB in national and international policies.

Another five-year consortium-run initiative, Asia Religious and Ethnic Freedom (Asia REF) implements projects across Asia. Asia REF highlights gender inclusion and creates safe spaces for female participation while maintaining awareness of the sensitivities involved. Consequently, most projects within this initiative have demonstrated significant progress on these issues despite inherent risks and difficulties.

But here I would like to share more detailed learnings from an eight-year initiative in Israel that I personally have directed to expand peaceful attitudes among religious communities who generally are perceived as stumbling blocks to a negotiated peace agreement of the Arab-Israeli conflict. In this initiative, we focused on engaging Jewish and Muslim religious leaders as part of the solution and not a weapon of war.

The participants discussed sacred texts that shed light on the core issues of the conflict. Through listening and learning from one another within their intrareligious groups, and then with those from the other religion, the leaders developed trust and a ‘religious language’ that formed the basis for recommendations on how to show respect for the other religion and advance peace politically. The leaders also implemented various practical activities to create greater knowledge and awareness of the religions in their communities.

Reflecting Search’s deeply held principle that inclusion is an effective way to advance positive change, we sought to recruit equal numbers of men and women to the initiative. However, the male Muslim leaders informed us that there were no female religious leaders so their participation would be impossible. Not wanting to give up on this principle, we recruited instead deeply religious Muslim women who were leaders in other fields e.g. education, social work, and law. Fortunately, we had no problem recruiting female Jewish leaders who were heads of organizations including women’s religious seminaries, but such different recruitment led to differing levels of religious knowledge between the sides.

There were various disagreements during the first iteration of the initiative that heightened gender tensions, but the crux came when the Muslim and Jewish women wanted to hold meetings to discuss texts without the men present. Some men became suspicious and objected to a perceived ‘feminist agenda’. They insisted on knowing what was being discussed. They refused to ‘allow’ the women to hold separate meetings without being present to supervise. Rather than battle this head-on which threatened the continuation of the project, we came to a compromise whereby a Muslim and Jewish male leader would attend the meetings …. but as observers only. After the first meeting the men no longer felt a need to join – their fears were allayed. They saw that the women were not ‘plotting to take over’! They simply wanted the intimacy and opportunity to discuss texts in a different way from the mixed gender setting.

The Muslim and Jewish women in general proved to be highly committed participants, running our social media platform, teaching students, and speaking at demonstrations. This level of commitment became even more dramatically evident after the October 7th Hamas attack. These women were the ones who spoke out fearlessly in public, calling for compassion for all sides. They set up neighborhood watches to nip in the bud interreligious tensions in the religiously mixed cities, paid condolence calls to bereaved families of all faiths, and spoke together to Muslim and Jewish groups to model the human face of both sides. In short, their leadership, steeped in religious principles, has been courageous, compassionate and deeply moving during this painful time when dehumanization of the other has run rampant.

In conclusion, here are 3 lessons we learned from this initiative about the role of religious women in advancing religious freedom and peacebuilding:

- Flexibility: When recruiting religious women, cast your net widely. It is useful to use the term religious ‘actors’ rather than the more limiting religious (overwhelmingly male) ‘leaders’ in work like this.

- Sensitivity: Including women on an equal footing with men may be seen as threatening traditional societal/religious structures and norms which results in ‘push-back’. The solution is to create an empowering experience for both women and men, and be sensitive to fears e.g. women’s lack of confidence and formal religious knowledge, and men’s loss of power and privilege. Studying sacred texts and using a religious lens to better explore constructive interpretations regarding the role of women and people from other religions, is a key to bringing about positive change.

- Adaptability: This is a crucial ingredient in the field of religion and peacebuilding. All too often we find ourselves constantly adapting according to context and external factors.

Religion is an identity marker for more than four-fifths of the world’s inhabitants according to Pew surveys[3]. For many it is the most important aspect of their identity. Hopefully our religions – and society as a whole – will understand the essential role women can play in peacebuilding and adapt accordingly. Our very survival may depend on it.

Sharon Rosen has served as Search for Common Ground’s Global Director of Religious Engagement since 2017. In this role, she oversees the development and project implementation of Search’s global religious engagement strategy.