A Gendered Approach to Remedies and Reparations for Yezidi Women

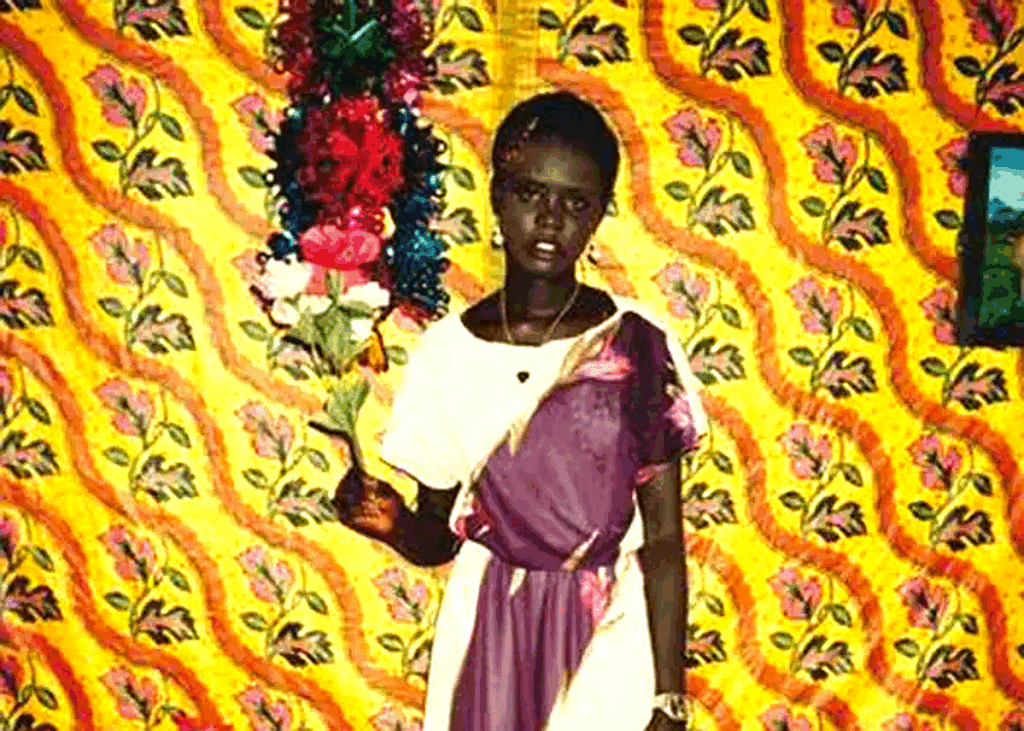

August 3rd marks a tragic day for the Yezidi community. On that day in 2014, the Islamic State (ISIS) launched one of the most brutal crimes of the 21st century, the genocidal campaign against the Yezidi community in Sinjar, Iraq. While thousands of Yezidi men were executed, Yezidi women and girls were subjected to distinct and devastating forms of gendered violence. Over 6,400 women and children were abducted and exploited. These atrocities were not incidental: they were deliberate tools of cultural erasure, targeting the Yezidi identity by assaulting the bodies, lives, and dignity of its women.

ISIS fighters abducted Yezidi girls and young women, bringing them to markets where they were sold as property to be brutally sexually enslaved. These markets of enslaved Yezidi women and girls were organized meticulously: only isolated instances of rape occurred outside ISIS’s rigid system of property. According to ISIS guidance, 80% were sold to individual ISIS fighters who held complete ownership over them. These fighters could gift or sell them to other fighters. The other 20% were ‘collective’ property held at military bases. While certain regulations existed–like ensuring that women and girls were not pregnant before they were sold—these regulations frequently were broken. More than a decade later, over 2,500 Yezidi women, girls and children remain missing, and the road to justice for survivors is being obstructed by political inaction, social stigma, and institutional inertia.

The Yezidi genocide was a deliberate and organized campaign by ISIS that involved mass executions, kidnappings, enslavement, and widespread, systematic sexual violence. The atrocities also included forced religious conversion, the militarization of children, mass displacement, and other severe human rights abuses. Along with women and children being enslaved and subjected to unimaginable cruelty, many Yezidi men and older women were executed on the spot.

The Current Status of the Yezidi Community in Iraq

The Yezidi community’s current status in Iraq must be understood through the lens of both historical trauma and ongoing systemic marginalization. Despite international recognition of the atrocities committed against them, the Yezidis remain one of the most vulnerable and marginalized groups in the region. They continue to face grave and persistent threats, stemming from, not only the past genocide, but also ongoing discrimination, political exclusion, and a near-total absence of justice.

Hate speech and societal discrimination remain widespread and largely unchallenged in both the Kurdistan Region and Federal Iraq. These forms of intolerance are not addressed through meaningful legislative action or political commitment, despite being widely recognized as root causes that, if left unchecked, can lead to further violence or genocide. The Yezidis suffer from political exclusion, a lack of justice, and limited access to decision-making platforms that affect their safety, rights, and future.

The Sinjar region remains unstable and militarized, with various armed groups operating outside government control. This environment prevents reconstruction and makes the safe return of displaced Yezidis nearly impossible. Ongoing conflict between regional actors, lack of coordinated security, and the absence of effective governance continue to endanger the community. Political underrepresentation further weakens the Yezidis’ ability to influence decisions that affect their right and future.

More than a decade after the genocide, justice remains largely symbolic. Most ISIS perpetrators remain unpunished, and Iraq’s legal response is limited to terrorism charges that lack due process and ignore crimes of genocide. Only a few prosecutions have occurred internationally, mainly in Europe—while survivors in Iraq see no real justice. The absence of accountability and the community’s exclusion from decision-making perpetuate impunity and leave Yezidis vulnerable to renewed violence. Although Yezidis specifically were targeted, ISIS also committed grave abuses against other religious and ethnic minority communities across Iraq and Syria. There is a real risk that these communities indigenous to Iraq, like the Yezidi, may not endure in this part of the world.

The Gendered Reality of Genocide

Measures to address the genocide and the situations of surviving women and children and those missing must go beyond symbolic gestures. Rather, they must be grounded in a gender-sensitive framework that addresses the unique and enduring consequences of these crimes.

Justice for survivors of gender-based violence also cannot be realized through a one-size-fits-all model. Yezidi women suffered deeply gender-specific forms of harm: rape, forced marriage, forced pregnancy, sexual slavery, psychological trauma. Many survivors continue to face severe mental health challenges and economic marginalization. Often widowed and displaced, they are left to rebuild their lives in the shadows of loss with no real legal or institutional support.

The 2005 UN Basic Principles and Guidelines on the Right to a Remedy and Reparation affirm that remedies and reparations must be “responsive to the needs of victims” and “take account of the special vulnerability of certain groups.” For Yezidi women, such remedies and reparations thus must be, not only restorative, but transformative, rebuilding both lives and systems.

ISIS’s systematic and strategic use of gender-based violence was wielded deliberately, as weapons of war and tools of cultural destruction. These crimes fractured family structures, dismantled community cohesion, and left long-lasting physical, emotional, and economic scars. Many women who returned from captivity came back to a world where every surviving male relative was gone. In their absence, the full weight of survival fell on their shoulders. Stripped of support, denied access to income, and burdened by trauma, these women were left to rebuild shattered lives alone — a testament to their resilience, but also a stark reminder of the profound injustices they endured.

Such layered harm cannot be addressed by financial compensation alone. A truly reparative justice model must offer healing, empowerment, and systemic change.

The Yazidi Female Survivors Law: A Starting Point

In 2021, Iraq passed the Yazidi Female Survivors Law (YSL), a landmark piece of legislation that marked a significant step in the country’s efforts to recognize and redress the atrocities committed by ISIS. The law officially acknowledges the crimes committed against the Yazidis and other minority groups—particularly women and girls—as acts of genocide. It specifically provides for reparations to female survivors of abduction and sexual violence by ISIS, including Yazidis and other minority communities.

The law promises financial compensation, access to housing and education, and mental health support for survivors of sexual violence.

YSL’s implementation represent critical steps toward addressing the suffering Yezidi survivors of ISIS atrocities have endured. While progress has been made in certain areas, obstacles remain that hinder the realization of justice and accountability and the search for the missing. Survivors continue to face bureaucratic hurdles, inconsistent access to remedies and reparations, and gaps in essential services such as education, rehabilitation, and employment.

A decade has passed since the ISIS atrocities, a sobering reminder that time continues to pass, and with it, the urgency of providing survivors with the justice they deserve. The path to an inclusive and effective reparations process requires concerted action from all actors, including the Iraqi government, the Kurdistan Regional Government, international partners, and local civil society organizations.

With the 11th anniversary of the Yezidi Genocide upon us, the window of opportunity to make meaningful strides in justice and reparations for survivors is narrowing. The coming years must be marked by a renewed commitment to overcoming these challenges, comprehensively implementing the provisions of the YSL, and ensuring that all survivors are supported and empowered.

Building a Gender-Sensitive Remedies and Reparations Framework

To be effective, remedies and reparations for Yezidi women must be comprehensive, inclusive, and survivor-led. They must be grounded in fair political representation in Iraq and protection from both the Iraqi central government and the Kurdistan Regional Government, with the Yezidi community’s demands taken seriously by both. Further, education reform is essential—teaching Iraq’s diverse history, including the Yezidi genocide, can help foster national unity and prevent future atrocities, as well as laws that criminalize hate speech and support from Iraqi officials who should lead inclusion efforts.

Remedies and reparations for Yezidi women should rest on four interdependent pillars that address the full range of harm experienced.

- Recognition and Symbolic Remedies and Reparations

Public recognition is essential to restoring dignity and validating survivors’ experiences. Symbolic actions can help address social stigma and foster communal healing and include:

- National remembrance days honoring Yezidi women and girls;

- Memorials and monuments co-designed with survivors;

- Formal public apologies by Iraqi state; and

- Educational campaigns to promote understanding and challenge stigma.

These measures can shift public narratives, acknowledge the depth of suffering, and foster a collective commitment to justice and remembrance.

- Psychosocial Support and Healthcare

Healing must begin with long-term, trauma-informed mental health care, adapted to the cultural and religious context of Yezidi communities, and include:

- Culturally sensitive counseling and psychological support for survivors of trauma;

- Safe housing for women facing domestic violence;

- Comprehensive reproductive and maternal healthcare, particularly for those impacted by forced pregnancies; and

- Integration of services into Iraq’s public health system to ensure sustainability and access.

This pillar acknowledges that mental and physical health are essential components of justice.

- Economic Redress and Empowerment

Justice must include economic empowerment. Without access to resources, education, and opportunity, survivors remain vulnerable and marginalized.

Such initiatives include:

- Direct financial compensation, proportional to the level of harm endured;

- Vocational training, education, and microfinance opportunities; and

- support women with children born of rape, including rights and protections.

Economic independence is not just a remedy, it is a preventive measure against future cycles of violence, poverty, and dependence.

- Representation and Participation

Yezidi women must be active participants, not passive recipients, in the design and implementation of measures to address the harm they have experienced, including by the:

- Inclusion of Yezidi women in decision-making bodies and reparations committees;

- Support for women-led NGOs and community organizations; and

- Funding and training for survivor-led programming in education, cultural preservation, and psychosocial support.

Survivors have the knowledge, vision, and resilience necessary to lead their communities toward healing. Their insights are essential, not optional.

Justice Beyond Compensation

Remedies and reparations are not merely financial transactions. They are mechanisms for recognition, restoration, and transformation. For Yezidi women, true justice must:

- Acknowledge the full spectrum of harm, physical, psychological, social, economic, and cultural;

- Include efforts to locate and rescue the missing, with international cooperation and forensic investigations;

- Offer care that addresses trauma, restores dignity, and rebuilds agency; and

- Create opportunities for self-determination and leadership, ensuring that women have a voice in their own recovery.

As long as thousands of Yezidi women and children are missing, justice remains incomplete. Reparations must include active efforts to search for the missing, identify the deceased, and support the families still waiting for answers.

Conclusion: From Survival to Justice

A gender-sensitive process does more than address past atrocities, it lays the foundation for a just and inclusive future. Such a process recognizes the unique suffering of Yezidi women, affirms their dignity, and restores their agency. It also helps build a society in which survivors are, not silenced or sidelined, but supported, heard, and empowered.

Justice delayed is not necessarily justice denied, but it must be justice designed, with and for survivors. Only through such an approach can the Yezidi community move from survival to justice and from trauma to transformation.

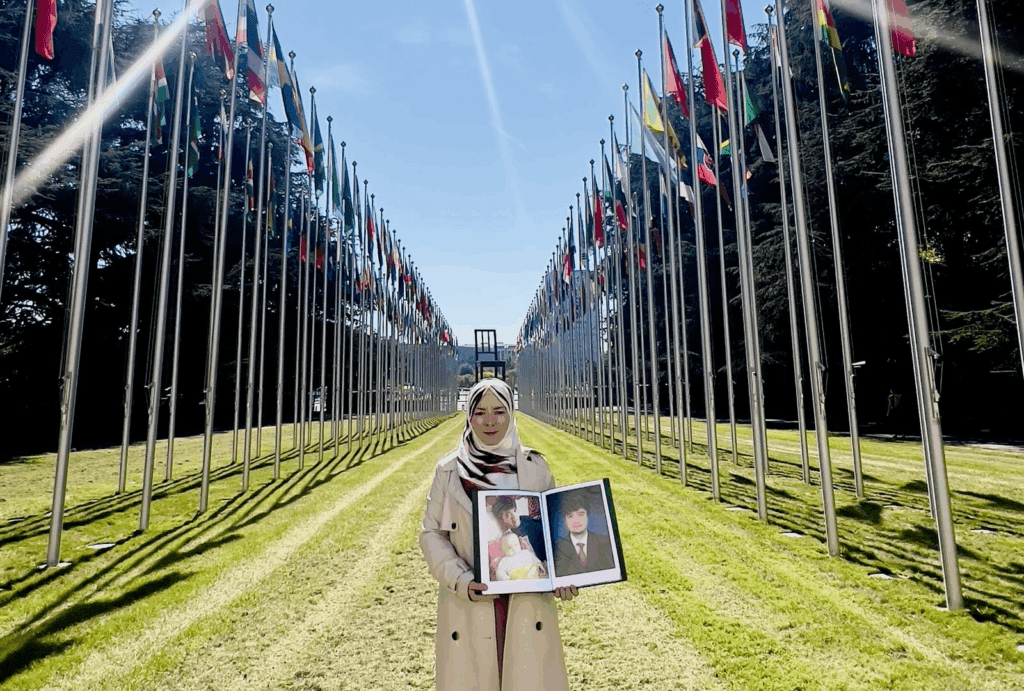

Hewan Omer is a Yezidi survivor of the 2014 ISIS genocide and currently serves as the Country Director of the Free Yezidi Foundation in Iraq. With over a decade of dedicated advocacy, she has championed the rights of Yezidi women and survivors of conflict-related violence. Hewan also champions the rights of persecuted minorities and contributes to the global movement for religious freedom and human rights.