Is working in support of freedom of religion or belief (FoRB) incompatible with women’s rights? Or is the opposite the case? That one right strengthens and reinforces the other? I raise these questions about two sets of rights as both a women’s rights and FoRB advocate in Latin America.

In recent years, significant positive changes have taken place for women’s rights in the Latin-American region. From laws on women’s political participation, to the recognition of care as a right and as work to be fairly redistributed, along with tackling gender-based violence and harassment, women’s rights movements have led the way to both position these issues as key public policy goals across the region and hold governments accountable on its progress.

During this same period, religious groups have strengthened their position in the public space, although with nuances across countries, influencing politics and public policy agendas, and even playing a key role on issues including eradicating hunger, fostering quality education, tackling climate change, and fostering gender equality.

At the same time, tensions have emerged that have served to reinforce a narrative that FoRB and women’s rights are conflicting rights, mainly due to the clash of agendas of feminist and religious groups on issues such as reproductive health and rights, which has contributed to increased polarization in the public space.

Do these tensions between certain agendas reflect a fundamental opposition between movements? To what extent do such encounters suggest an inherent conflict between women’s rights and FoRB? Or are there ways to mutually reinforce and advance both rights? If so, what are the areas of synergies and potential alliances in such an intersectional approach? Such an approach offers a roadmap to exploring how each can support the other, as it acknowledges how gender and religion, along with other identity makers like race, and class, differentially position people by creating diverse experiences of discrimination and opportunities for change.

Biases and assumptions in both worlds first need to be addressed to help fulfill the potential of joint FoRB and women’s rights efforts. It is key that the women’s rights movement overcome its secular bias and assumption that religion is an oppressive force per se. Professor Mariz Tadros from the Institute of International Studies at the University of Sussex has highlighted that advocating for a FoRB-sensitive reading of gender equality would provide an enhanced interpretative framework for redressing intersecting inequalities and implementing transformative policies.

There is also much to be done in the FoRB world to address its own biases and insularity that limits its transformative potential by often failing to address the unique challenges faced by women at the intersection of gender, religion, and social inequalities.

FoRB and women’s rights in human rights law

Are FoRB and women’s rights clashing rights? The short answer is no. As Heiner Bielefeld, the former UN Special Rapporteur on FoRB stressed, such apparent tension might be explained by the lack of clarity on the content, scope and limits of FoRB and its relationship with other human rights. Nazila Ghanea, as both a scholar and the current UN Special Rapporteur on Freedom or Religion or Belief, has underscored that the two rights are indivisible and interrelated and that one human right cannot be used to extinguish another. The bottom line is that FoRB does not protect religious dogmas, but the right of people freely to think, believe, or not believe.

There are key provisions in international law and instruments to bear in mind including the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (IPCPR– Article 5); the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW); and, in the Inter-American system, the American Convention on Human Rights (ACHR). And the Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action recognizes the role that religion and spirituality play in the lives of millions of women and its centrality for women to realize their full potential (Art. 24).

These laws and instruments underscore that these two rights are intertwined and can strengthen and advance each other. I want to offer a few insights about what can be done in practice to advance both, drawing on my work in these two worlds in Latin America and beyond.

The need for new narratives

New narratives are necessary to address the intertwined realities on the ground. These include that: women exercise their faith as part of their political agency; both the gender and religion dimensions of economic and social inequalities need to be acknowledged to address these inequities; women religious leaders and women of faith play relevant roles in both religious and civic spaces; religious actors, including Faith-Based Organizations (FBO), work meaningfully in support of the rights of women and girls, and the women’s rights movement works in support of the rights of women from religious minority communities.

Many of such realities are incorporated in the project Sembrando Esperanza (Sowing Hope), developed by the Maria Luisa de Moreno International Foundation (FIMLM), a Colombian FBO, and Wayuu indigenous women from La Guajira Colombia. This transformative initiative centers women’s leadership in tackling climate change and recovering degraded soil. Elevating such experiences can help strengthen the role of religious actors in promoting women’s rights and enhance the narrative of interdependence between these rights.

Promoting cross-movement solidarity

Women’s rights movements using FoRB language and mechanisms, and religious groups advocating for women and men equally fulfilling their FoRB rights and strengthening women’s agency in support of FoRB defense, would help create fertile soil for forging alliances and building bridges.

One example of such bridge building is the Chimpu Warmi Network, a women’s grassroots group promoting women’s land rights and confronting private mining land grabbing in Oruro, Bolivia. Toribia Lero, one of the more visible leaders, is a member of the Chamber of Deputies of Bolivia and the International Panel of Parliamentarians for Religious Freedom -IPPFoRB. As an indigenous organization, Chimpu Warmi has built strong ties with women’s rights and broader movements in the struggle for economic, social and cultural rights, as well as with FoRB organizations.

Below are some recommendations for building cross-movement alliances to help advance and connect FoRB and women’s rights:

- Explore areas of collaboration between FoRB and women’s rights groups: Such areas include: women’s leadership, violence and harassment against women, women and political participation, and social redistribution of care. For instance, in Envigado, Colombia, where I work with religious groups and FBOs, one of the churches runs a program to alleviate care burdens of elder women, providing support in such activities and contributing to women´s self-care and poverty reduction.

- Build alliances through advocating in broader movements: Connect with initiatives promoting issues including indigenous land rights, climate change, and development. Many human rights organizations or movements, while not focusing exclusively on women’s rights, are strongly committed to such work.

- Do not assume that the religious sector and the women’s rights movements are homogeneous: Explore the large number and diversity of organizations in both worlds, be open to finding commonalities, and connect and shape shared agendas with other organizations to strengthen your network and expand your impact.

- Cultivate trust and create long-term relationships: Because building alliances requires creating trust, which demands patience, commit to long-term dialogue, transparency, mutual learning and support, as well as creating space for disagreements.

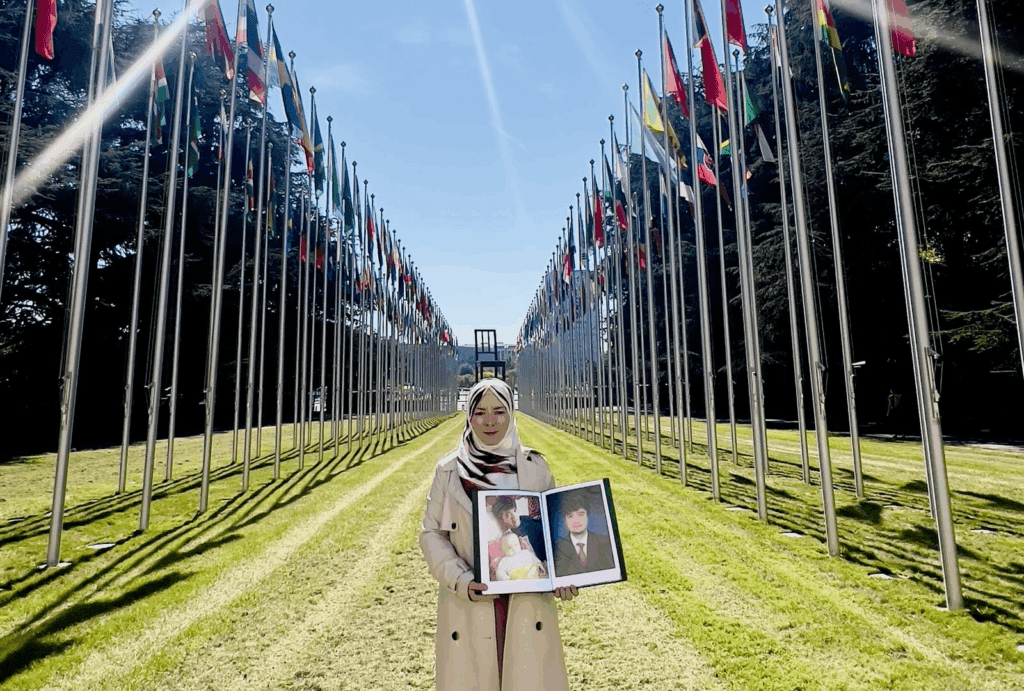

Expanding women’s leadership and amplifying their voices in the FoRB movement

Women of faith, who often experience gender-based discrimination in both civic and religious spaces, are crucial actors in bridging the gap between FoRB and women’s rights and building more inclusive movements in both worlds. A key step to catalyze this integrative role is addressing the gender gap in FoRB leadership and policy development.

With formal mechanisms to advance FoRB flourishing in certain countries in the region, this is an opportune time to promote women’s leadership. In Colombia, significant progress on FoRB has crystalized in the creation of about 350 local Religious Freedom Committees (RFCs), These multi-stakeholder, social dialogue spaces promote FoRB through a decentralized, inclusive approach. However, a gender gap exists given the small proportion of female religious leaders (21.2%) compared to male religious leaders (78.8%).

Below are some recommendations to strengthen women’s leadership in FoRB:

- Amplify and celebrate women as FoRB leaders and their essential role in promoting gender equality, development and peacebuilding: Women role models and pioneers are key to shifting narratives and encouraging women’s leadership.

- Women need to be at the table: Explore ways to include women as decision makers in all stages of FoRB policymaking and implementation as well as in formal FoRB mechanisms. This might include: reserving a number of positions for women to serve as representatives, including women religious leaders, women of faith, and FoRB advocates; collecting and analyzing qualitative and quantitative data that disaggregates participation and impact by gender in FoRB spaces; and tracking barriers to women’s leadership. FoRB Women’s Alliance in its report, Women at the Table, explored this and other dimensions of the issue.

- Create safe spaces: Such safe spaces that help protect women against all forms of violence and harassment and enable solidarity building among women are necessary preconditions for women to experience and advocate for FoRB and women’s rights.

- Organize trainings: These trainings, for women, women of faith, advocates and male allies, in areas including leadership-development and coalition building in FoRB and women’s rights, are key for women to lead on FoRB.

- Engage a wide spectrum of women of diverse and no faiths: Women play many different kinds of roles within religious and secular groups and FBOs. For instance, spouses of pastors often are leaders in their communities. It also is important to support and fund initiatives led by women with these diverse faith backgrounds to enable them to share experiences and join efforts in support of FoRB and women’s rights.

- Foster intergenerational dialogue and solidarity: It is important to support young women leaders to help elevate their voices and access key opportunities to develop their agency. In turn, they can offer older generations innovative and creative perspectives, while learning from them.

A case study: Partnering for development

Religious actors, including FBOs, are key allies to achieve sustainable development. In fact, there is a strong correlation between religious freedom, economic stability and women’s empowerment. A study conducted by the UNDP and the Ministry of Internal Affairs in Colombia (2022) found that religious actors, including FBOs, were key to achieving Sustainable Development Goals (SDG), including SDG5 on gender equality. This study highlights that such contributions to SDGs largely benefit women and girls, that women do much of the necessary work as volunteers, and that actors from the religious sector contributed substantially to development efforts, along with the reduction of violence and harassment and, the relevance of women’s leadership, among other issues. A second study conducted by the UNDP in Argentina (2019) produced similar findings.

Amplifying the contribution of women from both the FoRB and women’s rights sectors to development can help shift the narrative that FoRB and women’s rights are in conflict. Key to this shift is what women FoRB leaders and activists bring to the table: access to difficult-to-reach areas, strong bounds in impoverished communities, the significance of faith as a factor supporting women’s resilience; their experience working to support communities in crisis, and their efforts to build and repair the social fabric. These are just a few examples of why partnering with women religious actors is key. Women’s rights organizations and movements have not only led on this cause but are the best possible allies to help expand the impact and the transformative effect of what the religious sector already is doing on issues of shared interest.

Towards an intersectional FoRB framing and promotion

Intersectionality is not just a framework. It is a necessary strategy to meaningfully advance both FoRB and women’s rights. In Latin America, this lens—often referred to as enfoque diferencial—has been key in shaping more inclusive policies and practices. The bottom line is that intersectionality works! And much needs to be done.

Putting intersectionality into practice means centering the voices and leadership of women who live at the intersections of multiple forms of exclusion — including members of religious minority communities such as indigenous peoples, Afro-descendant communities, and other marginalized groups. Their lived experiences must inform the identification of the specific and differentiated barriers they face, but also the design and implementation of transformative responses that reflect their realities and aspirations.

Promoting the interdependence between FoRB and women’s rights is not just about bridging two seemingly distant worlds; it is about unlocking the full potential of both. It requires courage to challenge persisting narratives, creativity and openness to forge new alliances, and humility to listen across differences. Latin America, with its rich history of religious pluralism and women´s mobilization, has a unique opportunity to lead the way. As I continue to answer my own questions, I hope these reflections are helpful for you to answer yours.

Viviana Osorio Pérez is a FoRB and women’s rights advocate and policy advisor based in Colombia. She is the co-chair of the Latin America Working Group of the IRF Roundtable, a FoRB Fellow, and Chair for Latin America of the Global Youth Summit for FoRB. She also is a Senior Fellow on Economic and Social Inequities of the Atlantic Institute and London School of Economics. With a longstanding commitment to advancing women’s equality, she brings extensive experience promoting women’s rights and, more recently, integrating freedom of religion or belief (FoRB) into her advocacy. Her work bridges global and local contexts, fostering transgenerational, interreligious, and cross-movement solidarity