America’s international religious engagement sought to advance religious freedom abroad and combat religious extremism. The government took on this engagement in two waves. The first was in the 90s when liberals and conservatives united in a common cause on issues such as freedom for Tibetans and protection for religious minorities in Iran. Adapting to this first wave, the U.S. government began to rely on the 1971 Supreme Court case Lemon v. Kurtzman as practical guidance for civil servants to engage religion abroad. In Lemon, the court created a three-part test for determining when a law violates the Establishment Clause, concluding that for a law to comply with the Establishment Clause, it must (1) have a secular purpose; (2) have a predominantly secular effect; and (3) not foster “excessive entanglement” between government and religion. Well-meaning bureaucrats then adapted this “Lemon test” for the civil service.

The Bush Administration spurred on the second wave with its establishment of the Office of Faith-Based and Neighborhood Partners across multiple agencies, ranging from the Department of Commerce to USAID. This office was established in 2001 partially to help prevent anti-Muslim blowback from the Global War on Terror and respond to demands from the American people for faith engagement. Over the past two decades, while partisan disputes over these offices have changed their mission, impact, and focus, Lemon has remained their operational touchstone, guiding their work both domestically and internationally.

Lemon remains the touchstone today, despite the U.S. Supreme Court’s 2022 abandonment of the Lemon test in the case of Kennedy v. Bremerton School District. In a 6-3 decision, the Court held that the government may not suppress an individual from engaging in personal religious observance, as doing so would violate an individual’s free exercise rights. The Free Exercise and Free Speech Clauses of the First Amendment protect an individual engaging in such observance from government reprisal; the Constitution neither mandates nor permits the government to suppress such religious expression. Bremerton replaces the Lemon test with a consideration of “historical practices and understandings,” – a “history and traditions test.”

Offices in the U.S. federal government that engage in religion and religious freedom have not updated their Establishment Clause guidance to reflect Bremerton’s history and tradition approach. The DOJ last updated their guidance in 2018; the Department of Defense in 2017; and the U.S. Agency for International Development in 2019—the most recent. The Department of State offers no publicly available resources.

These resources were developed in response to President Trump’s 2017 Executive Order 13798, which called for the U.S. Government to prioritize international religious freedom, provide foreign assistance funding for religious freedom, integrate religious freedom into diplomacy, train officials on religious freedom, and develop economic tools to advance religious freedom. In 2020, the Trump administration reaffirmed the importance of these directives with Executive Order 13926.

In foreign affairs, Bremerton empowers the government to engage religious communities in pursuit of diplomatic, development, security, and FORB goals. One would think that after Bremerton—a revolution for the possibilities of religious engagement—federal agencies would, at the least, provide updated guidance or, at the most, take advantage of the new opportunities Bremerton provides to engage religion more. So why haven’t they?

The Establishment Clause and Foreign Affairs: Lemon’s Legal Culture

The role of the Establishment Clause in foreign affairs is unclear and debated. In practice, there are two realities—that of the law, and that of the law as it is understood by government workers in foreign operations. In the former case, many lawyers would claim that the Establishment Clause under current jurisprudence does not apply to U.S. foreign affairs because the president’s power to conduct these affairs arises from his role as commander-in-chief and head of the executive branch. Per Curtiss-Wright, the President is the “sole organ” in international affairs. Textually, there is no suggestion that the Establishment Clause applies to foreign affairs. In both historical discussions at the time the Establishment Clause was drafted and records of debates, the evidence indicates that the purpose of the clause was “to prevent the creation of a nationally-sanctioned religion that stifled the freedom of state sovereignty and the liberties of citizens.” I would concur with those who assert that there is no historical evidence to suggest that the Establishment Clause applies to foreign affairs. In fact, as I will note later, religious engagement took a prominent role in American foreign policy early on in American history.

The goal of the Framers was to prevent the federal government from establishing a specific organized religion – or no “Church of England” in the United States. The Establishment Clause acts as a restraint on the federal government by protecting state governments, which did establish state religions, from a federal government imposing a national religion on states and their citizens. As a function of federalism, the Establishment Clause is purely domestic. It is difficult to imagine any action taken by the President in foreign affairs that would establish a state religion aside from swearing fealty to the Pope in the Apostolic Palace.

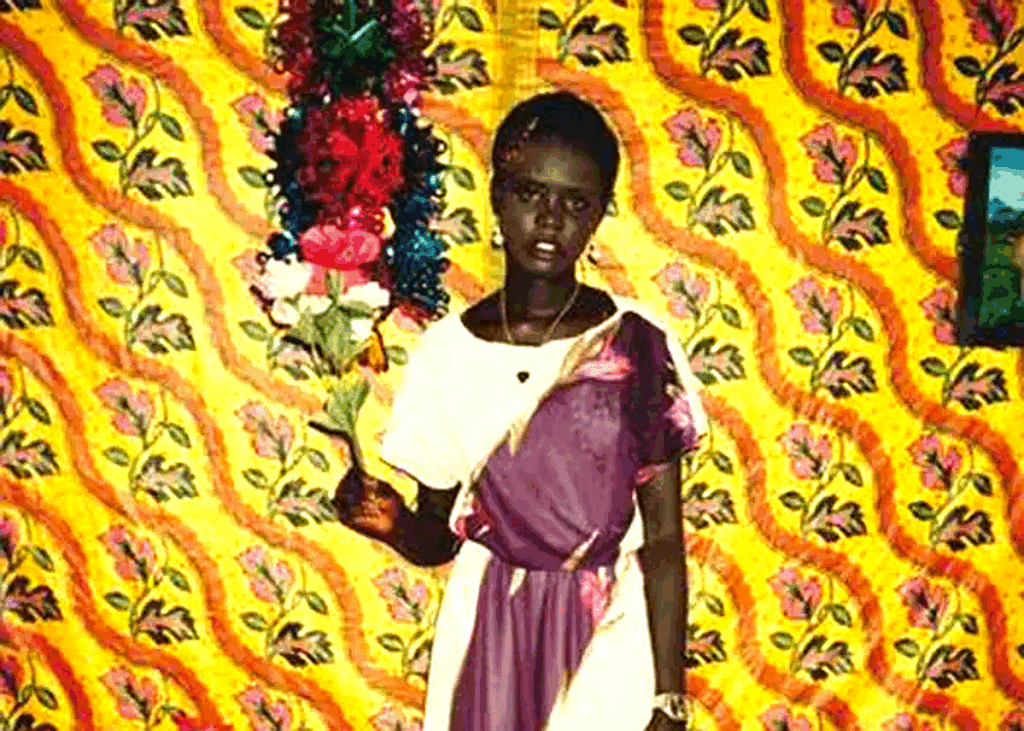

In short, the U.S. government can do what is necessary with religious leaders and in the area of freedom of religion or belief abroad, even supporting some specific religious beliefs over others, if doing so achieves national objectives. For example, supporting religious leaders in Gambia who oppose female genital mutilation would be a perfectly legal activity and fulfill a key goal of advancing U.S. foreign policy: protecting women.

Whether one should or should not undertake these actions is debatable, whether they are legal, is not.

Despite the Establishment Clause’s legal irrelevance to foreign affairs, the laws we adopt for domestic life in the United States have become the culture we bring into foreign affairs. The basic way that people understand religious freedom in day-to-day life in the United States has become the de facto practice of religious freedom in foreign policy because citizens largely staff our foreign affairs agencies. Though the law does not apply, the principles of the law are nonetheless applied. Domestic law becomes a cultural touchstone for how the U.S. undertakes religious engagement abroad.

Domestic law has become this touchstone because that is what is taught to civil servants. For example, USAID’s 2019 guidance uses the following slide which is the Lemon test:

This guidance reflects a Lemon culture and a bureaucratic practice taught to thousands that, not only prevents religious engagement, but also teaches employees how not to engage religion. USAID employees have an unnecessarily restrictive understanding of religious engagement because agency guidance has not been updated since Bremerton. Failure to update agency guidance is either a simple oversight by every federal agency or a deliberate choice of agencies that prefer a restrictive culture of religious engagement to a permissive one.

There are two realities—that of the law/practice, and that of the law/practice as it is understood by government workers in foreign operations. In the case of religious engagement by government, the law and practices being taught are restrictive, with no basis in actual jurisprudence.

Bremerton: A New Culture of Religious Engagement

After Bremerton, USAID can seek to support, engage, and uplift religious leaders who are friendly to American goals and interests abroad, thereby expanding the range of options the agency has to engage on an issue like FGM, peace building, trauma training and community development, or to counter extremism. Again—whether AID should or should not do this is up for debate—but the barrier is not the Establishment Clause. The barrier is whether administrations and agencies decide to adapt to new legal touchstones for religious engagement.

If someone polled a random DOS or AID employee on the idea of specifically uplifting the voices of religious leaders who have views favorable to American interests, there’s a solid chance they’d cite the Establishment Clause and declare the act illegal. Maybe they’d even cite Lemon. I’d argue that the U.S. should discriminate between religious groups. We should support those who love freedom, liberty, and support women, and refuse to engage or provide taxpayer dollars to those that hate freedom, liberty, and women.

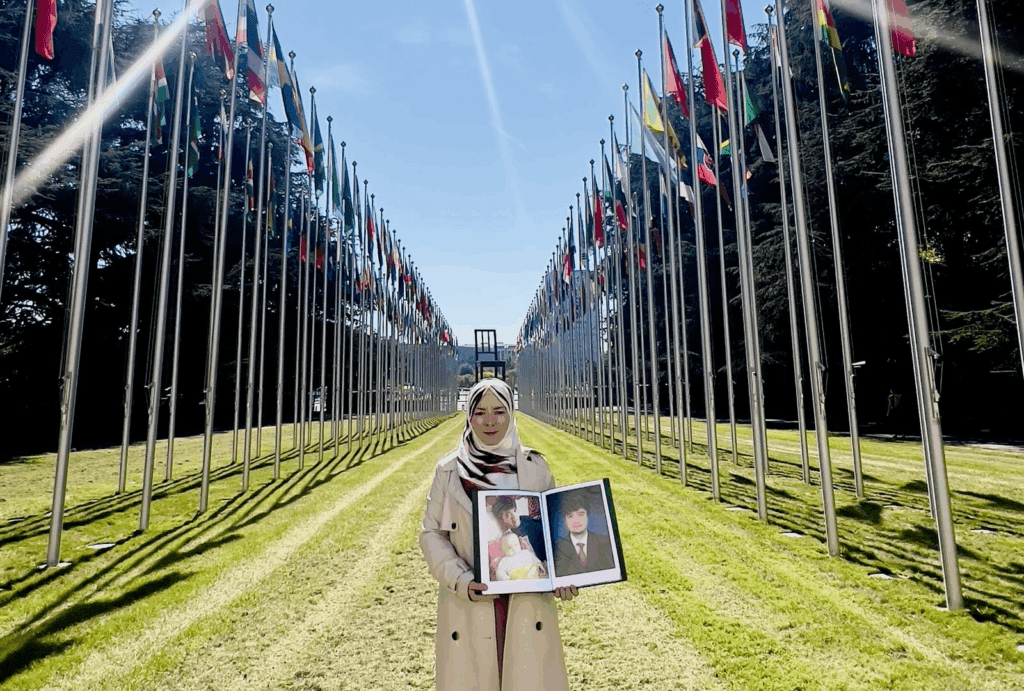

A modern example would be the use of U.S. taxpayer dollars to create a platform that supports women for Afghan scholars resisting the Taliban. This aid would mean the U.S. government is directly supporting one religious view over another, favoring women’s rights over a hostile state that harbors terrorists. A platform like this would not pass the Lemon test used in the USAID slide since it would endorse one religious view over another. Using Bremerton’s history and tradition test, this platform would be acceptable and in line with contemporary Establishment Clause jurisprudence, which calls for the U.S. government to look to American history and traditions.

In foreign affairs, the U.S. has directly supported missionaries and religious schools through the Civilization Fund Act of 1819. This support is an early indicator that the founders did not envision the Establishment Clause limiting religious engagement in foreign affairs. Through this Act, U.S. dollars went to support Christian missionary activities and create Christian church schools. The government directly paid for religious conversion and education. In addition, prayer in schools and government buildings has been a longstanding tradition of the U.S. government and in foreign engagements. The cold war itself was fought against, not only communism, but explicitly violent atheism—with religion taking a greater role in American foreign policy.

Throughout American history, religion has had a changing but consistent and prominent role in foreign affairs.

In foreign affairs, Bremerton opens the door to religious engagement in line with tradition and history. That history is one in which the U.S. government directly has advocated for religious and civilizational values that advance the rights that Americans hold dear, without tests like Lemon that artificially restrict religious engagement. Bremerton calls back to the full history of the American state, and we can draw from that full history for models and methods of religious engagement. We do not need to restrict ourselves to examples of foreign operations from 1971-2022 undertaken under the Lemon test paradigm.

There are offices at many agencies, such as the Office of Faith-Based and Neighborhood Partnerships or the Office of the Ambassador for Religious Freedom, that can take the lead in ensuring that up-to-date Establishment Clause materials are provided to agencies and the public. Such dissemination should be done regularly if the Establishment Clause is going to be adapted for foreign operations as a cultural touchstone—which administrations seem to want to do. If not, we end up where we are now, with agency approaches that can pick and choose what Establishment Clause jurisprudence they follow.

Religion and Women

All around the world, religious people and groups daily shape the political, economic, and social lives of billions. Our interpretation of the five words of the Establishment Clause determines how the U.S. government, on behalf of the American people, treat all of those people: whether we support anti-extremist leaders, whether we provide peace and trauma training, and whether we effectively support women in their effort to advance their rights around the world and help their communities thrive.

While U.S. agencies may feel comfortable avoiding changing their guidance—since that’s the easy and safe route, women and children who face religious persecution or whose rights and safety are determined by religion have no such luxury.

Advancing women’s rights through religion after Bremerton should be understood to involve using FORB to advance women’s free practice of religion and support their activities to advance themselves and their communities. The U.S. government can and should uplift and support women and combat violent extremism and the hatred and oppression of women, and oppose those who endanger American interests. Agencies should provide new guidance to their staff to ensure that the U.S. government may, on behalf of the American people, engage with religion to advance women’s rights, safety, and security abroad.

Julia Schiwal is a historian residing in Washington, D.C. who studies war, peace, and international politics. She has written on diverse issues, ranging from advanced technology threats to international religious freedom and engagement. She has worked in government on issues related to religious engagement, technology, and foreign policy, especially in peace processes and international peace agreements. She has a master’s degree in imperial and colonial studies from the George Washington University and a bachelor’s in global humanities and religions from the University of Montana.